Jyoti Bharadwaj launched TeaFit in 2021, offering a range of unsweetened iced tea and herbal blends. She has since added unsweetened premixes to the portfolio. For India, a country with a large population suffering from diabetes, she says, unsweetened beverages were needed, and tea offered the perfect vehicle. More recently, Jyoti was featured on Shark Tank India, where celebrity entrepreneurs agreed to invest INRs 50,00,000 rupees (USD $60,000) in the brand. Jyoti talks about functional, condition-specific, and ready-to-drink tea and how her brand is helping tea shed its fussy image.

Aravinda Anantharaman: Will you share the story of how TeaFit came to be?

Jyoti Bharadwaj: I have had a rather longer route to entrepreneurship. I wasn’t born to be an entrepreneur, nor do I come from a family of business people. We are the typical service-class Indian family that focuses on education and grades, and you become an engineer, get into consulting, and do an MBA, so that’s the route I had for myself as well. So, I am an engineer. And then, I did my MBA from the Indian School of Business. Somewhere in the middle, for a couple of years. I did work in a large IT company. But I think that taught me what I don’t enjoy or am not cut out to do. And thankfully, I learned that fairly early in life. After that, I did my MBA and have been building startups. So, after two successful startups, I was honestly beginning to get a bit bored. Liabilities were taken care of, I had paid off my huge education loan, and I had a nice house in Bombay. And that was pretty much it. I was taken care of in that sense. So that itch to do something meaningful beyond the next job, I think, was gnawing at me a little bit. And also, my kids were really young. I was not enjoying staying away from my young ones for so long every day.

I have traveled to Japan quite a few times. And I really enjoyed the unsweetened beverage space of Japan. And just the pride the Japanese folks, have in traditional cuisines that somehow pick up or resonate from their traditional teas, herbs, and botanicals. And so for every Cola or sugary beverage, you will find in vending machines 20 different types of teas that are made from greens, from oolong tea to matcha, you name it. And I was blown away by the kind of selection there and the access people had to good products or products that are good for you.

When I visited the beverage aisle here back home, there were just three broad categories: Cola, fruit-based/sugar-based beverages, and energy drinks, and somewhere in the middle is where you have to make a choice. The whole game is pinned on the idea the Indian consumer wants things sweet. When you look at the options, they are so limited that you can’t really blame the typical consumer for picking what they do.

Aravinda: So, what is TeaFit all about?

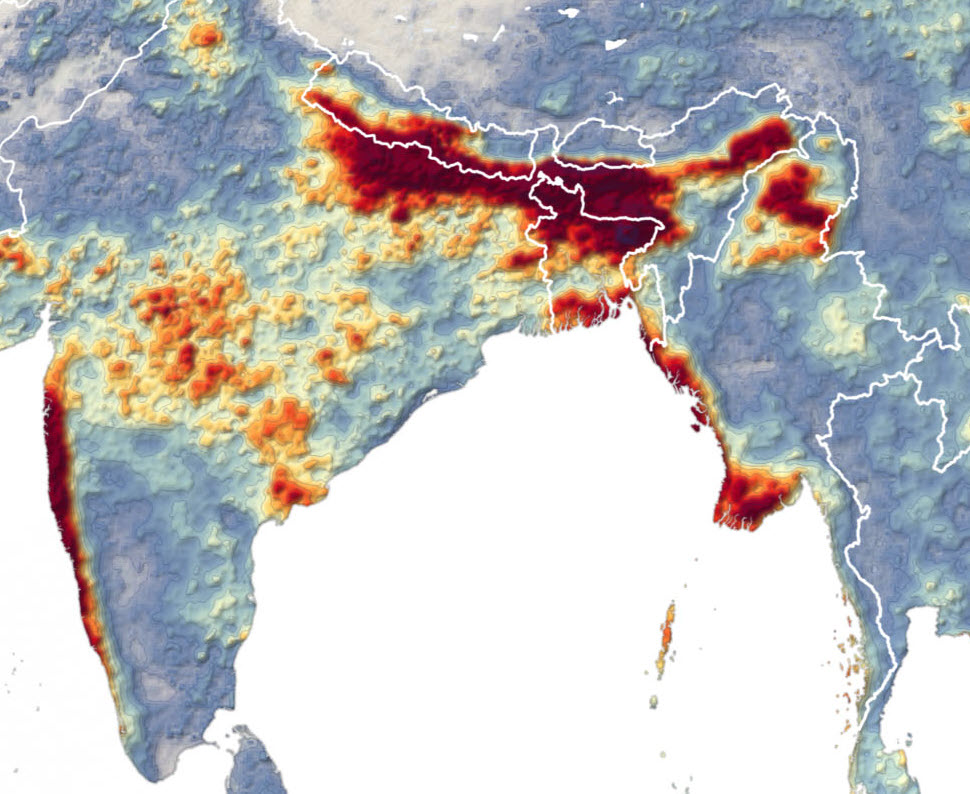

Jyoti: I come from a diabetic family. My parents are diabetic, and I am borderline diabetic. India now has ten crore (100 million) diagnosed diabetics. It’s a serious number, and somewhere I felt that the responsibility lies with irresponsible brands in pushing such products. Mainstream marketing and kind of, making it cool to have this ten times a day, and associating it with aspiration, with happiness, and with, you know, all of the other strokes of marketing. So, like, the seed was there in a way to build something responsible, to build something intentional, where it’s not just less bad for you, things that are good for you that can be bottled up.

There are many herbal recipes from our own Ayurveda. We selected tea as a base to make the blends flavorful and light on the palate and not douse everything with loud flavor and sugar. So that’s where it came from, a very personal place, but I’m glad it found resonance in the larger customer base.

I would also like to say that with all the destruction that COVID caused, I think a small glimmer of hope that it gave everybody was that people got conscious of what they were consuming overnight, and label awareness grew. They wanted to read the back of the label slightly more than they did previously. So if earlier you saw a product that says ‘Good for you,’ or ‘Increases height,’ or ‘Loses weight,’ they would pick it up, but today, they flip the bottle around and see what’s actually there in the nutritional panel. So that’s, in a rather big nutshell, my journey. I’m glad that I’m representing responsible brands in the space, and it’s an absolute privilege to do what I do and to survive the early days of difficult days of the business to be here to be talking to you today.

Aravinda: How difficult was TeaFit to formulate and produce? And what did you have to do to achieve healthful flavor? In India, I also feel that we have become so used to things being slightly exaggerated in flavors, right? More spice, more sweet, deep fried, and we tend to associate those with better taste. I think that’s sort of what we’ve been given. So, on the production side, what did you have to do to ensure you still retain the integrity of what you wanted the product to have without compromising on flavor?

Jyoti: I would like to take a minute to highlight that I was clueless. I was as clueless about the business as the next person on the street. So it did take me longer to figure out. I literally Googled on day one of quitting my job, ‘How do you make iced tea at scale’? Everything started with Google. And then, very soon realized there was no way I could do this myself; I needed to find people who knew more than me playing Einstein. So I would say that whatever success I’ve achieved, I think that’s more to do with the kind of talent I have been able to convince to come on board than being able to solve things quickly myself.

So I researched the top leaders in Ayurveda, who are the product heads of large companies like Himalaya Herbal, and then I went and knocked on their door and begged them to come on board and work on this idea with me. My broad stroke problem statement was that the product we want is a healthy beverage with no sugar and a base in tea. It features herbs blended in combinations that help you fight the stresses of modern life. You’re always on the go; you’re always ordering in food, something that would, you know, that could help you with digestion, that could help you feel light, energizing, that doesn’t add to the sleepiness.

The initial journey was difficult until I found the right people to work with. I feel that when you start out with the right intention, you find good people to work with. So, I would like to highlight a pharma company in the Ayurvedic space they are based in Nashik called Rev Pharma. I was a one-woman army, they could just shut the door in my face, but they didn’t; they respected the idea. And they allowed me and my team to utilize the facility to do the entire product development, do the tinkering on Ayurvedic formulation, and see what kind of extracts we would need. Would we need powdered extracts, liquid extracts, or spray-dried extracts? But we did struggle to come to the right flavor initially in the absence of sugar because first, you take out sugar, then you add, you know, a blend of 15 herbs.

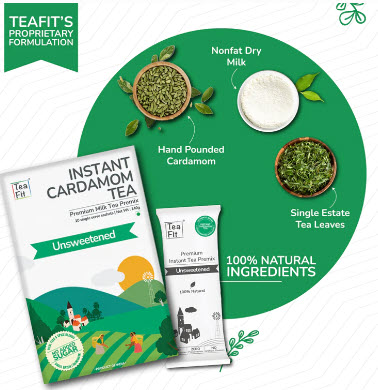

We also didn’t want to lose the delicate flavor, the notes of the tea. We use our tea from a single-origin farm in Assam called Zendai Tea Estate and another similar state in Kerala for green tea. Initially, the tea would be too strong, and it would just be very astringent. It would have lost its finer top notes. So then we redid the entire fabrication of the brewing process. The manufacturing plants in India are typically made for either carbonated beverages or they’re made for fruit-based beverages. So for our tea brewing and herb brewing, we had to set up a whole different line wherein you do it outside the filling line at the temperature you want and then introduce the brew into the main filling line. So it did take a while for us to figure it out. Lots of failed experiments where an entire batch was on the floor because the filter got choked. So we’ve also had a journey where because we have done things from the ground up, seen every possible thing that could go wrong, and therefore, you know, we are now doing it right.

Aravinda: So how long did it take from you know the point when you started the R&D and to, say the first batch that you said, Okay, I think we’ve cracked it?

Joyti: Fourteen months is what it took, from the sketch of the product. And I also was a little bit ziddii*, in the sense that I didn’t want to take shortcuts, so I didn’t want a bottle that existed. So this bottle, you see, was designed by the Indian School of Design and Innovation, so it did take me some time to figure out who would do the bottles for us. And when you’re new, you don’t know the limitations of the industry. So I didn’t know that if you have a bottle like this, it’s hard for you to do hot fill because the bottle collapses so I also figured out a lot of things along the way like I said, I’ve made every mistake I could have made, and I am still alive.

Aravinda: That itself calls for congratulations. Why tea? Why was your starting point tea?

Joyti: I felt the kind of products I wanted to make was hard to do in a fruit-based beverage, and power drinks I didn’t want to touch in the beginning because, like I was anti-everything that carbonated drinks stood for. And also like I’m a tea person. I like tea. So it started as a pet project of mine, I used to do it in the kitchen, you know, hibiscus tea, and all sorts of tea, barley tea when I came back from Japan, and people started liking it. So I was like, this is one thing I know how to do. And let me work on this. I also felt like it allowed for the botanicals to find a good home for being effective and finding a synergized flavor. If you put the same thing in juices, it just tastes very off.

My Nanaji (maternal grandfather) used to make black lemon black tea, which is legendary in our whole locality. He’s no more; God bless his soul. But I think I was hooked on that. So the first two or three things I wanted: I wanted his lemon black tea. And also, Aravinda, from a business perspective, the drink itself was alien to the Indian consumer. There was no unsweetened drink per se like there was an odd water or a couple of other drinks like that, but there was no drink with a personality of its own and was unsweetened. So there was a bit of unfamiliarity to begin with. And we didn’t want to make it further unfamiliar, like adding two steps of alienation by creating a flavor that’s not mainstream. We wanted to go with the two most mainstream flavors which are lemon and peach in iced tea, and give that to customers saying, “Look, your lemon and peach iced tea could be this.” So that’s what we wanted to go ahead with, just making it less complex as an introduction or making it less complex to decide on the first purchase, the first trial.

As a business owner, your holy grail is trials and then eventually the beats. So for a bootstrapped brand, if you have to pursue trials, either your packaging has to be phenomenal, the brand has to be really catchy and simple for you to understand, or the product has to be really simple for you to understand. So for all of these reasons, we wanted to keep the complications kind of as minimum as possible. We made lemon black tea, and we did a peach drink tea, and we did barley tea which was something that I personally liked a lot it has immense health benefits, and it will be tragic if people don’t get to try it. These are the three products that we started with.

Aravinda: Would you say health is still the main marketing angle for tea? Do you think people respond to health and wellness as in the marketing conversations, or is it flavor?

Jyoti: As a product-first company, I will say if you don’t have a strong product, no amount of positioning of the product will really get the customer pull. So first, the product has to be incredibly strong, which means it has to check all the boxes. If you ask me what is important – is the health angle important, is the flavor important, is the price point important, is the availability important – I would say all of these four, if they are in place, only then there’s a hope that you know the customer will discover you, will decide to part with his money to try your product. So in my case, I was hell-bent on finding the right flavor. We wanted customers to come for the flavor. You flex on the flavor, you know? Health is something we take care of, it’s something that is in the product, but you come for the flavor.

Even the premixes that we have launched, milk tea premixes, are unsweetened, but if you drink the product, it is phenomenal. We could have put fillers in it or done all kinds of shortcuts to arrive at a cheaper product that probably would appeal to a wider range of audiences. But we didn’t. We were like, this is what we’ll do, we’ll find our consumers, maybe everybody’s not my customer. It’s important to know how wide a net you want to cast because that will determine what kind of product you will develop.

Aravinda: And with marketing, have you relied heavily on online and digital, or have you gone for a bit of both?

Jyoti: We knew that we have to be present in the offline touchpoints, wherever impulse buying happens. And so we our first point of sale was not online or on our website. It was Nature’s Basket stores in Mumbai. We started with a few of them. And in the longer view, if I take a longer view of things, I would say that distribution is probably more important than anything else regarding the beverage business. By that, I mean trade, finding the right channels, setting up distributors, and ensuring your product is available. Because even after Shark Tank, I feel like I lost a lot of customers, or maybe I advertised for my competitors in that sense because our distribution was not there. If somebody in Delhi went to buy a TeaFit after watching us on Shark Tank, we were not available. A lot of marketing without distribution is marketing for the competitor. So we’ve not done a lot of marketing; we are looking to focus on building deeper distribution within Mumbai, within Pune, and then spread radially from there. And online and commerce, we are pretty much everywhere today, on Big Basket, Blinkit, and these platforms. So we want to be wherever the customer is, in the best, most cost-efficient way. And most of our marketing is organic, we do some marketing on the platforms where they’re on. Like, if you’re an Amazon, we’ll do some Marketing on Amazon. And similarly, for the e-commerce platforms, we do some marketing in stores where we are, we do sampling activities.

A big blitz will get you trials, right? It will get your eyeballs, will definitely make people curious, and make them try. But if you don’t have the right product, they will not return. So I always insist that it is not the first PO or the first order that matters, but it’s also the second PO, right? The second order, or, you know, the second time the distributor calls you and says, I need to talk. And those are the real markers of where the business is going.

Aravinda: Tell me about the Shark Tank experience. Why did you choose to go? What happened? How was it? And how has it been post that?

Joyti: I don’t think I chose it. I think it chose me because there were so many people who applied for it. And all great businesses. Many far ahead in the journey than me. In fact, I applied last year, also. I was like two weeks, two months into the business, I had done a sum total of Rs 20,000 in revenue and applied. So the guts were always there. And I did get through all the rounds, even in the first season. But I was traveling when they wanted to come, so I had to skip it. This season, I didn’t apply with any hopes. Honestly, I’ve seen all 85 episodes of Shark Tank to know that it’s almost a fluke that you make it or it’s a stroke of luck. So I would say that probably my story resonated with them. There are a couple of rounds of applications wherein they ask what’s your big vision? What’s the big idea? What is it that you’re building? And if you get shortlisted for a second round, which is also written down but fairly detailed in terms of revenue, product market fit, and your footprints, all of that. And then, you have to submit a three-minute video pitch to them. If they like it, they call you. And that day, I didn’t have any baby care at home. So I took my kids with me on the day of the auditions. So whoever is in the audition must attend the final shoot. So I had to take them on the final shoot even though I was unsure how the kids would behave. But I guess it went well. I am generally not a very camera-friendly person. I prepped for it, and then I went. I had done the business in and out from day one alone. So those answers you will always have, and I felt like that came through well in the show. We got a lot of love. Our phone didn’t stop ringing for weeks. We had 300-350 distributor inquiries overnight; sales skyrocketed, and the website shut down… so all of the good things a business faces, we faced all of that, and it has given us like catapult us into a different stratosphere.

So I was playing at a very small business level, now I would say that, you know, we are fighting bigger problems. I have a bigger team overnight now. I was doing a couple of interns and a friend. Now I’ll have like a legitimate team of people. More than anything, people know about the brand. People know what we do. So the kind of exposure the brand gets makes up for any inhibitions you have as a founder. If you’re a consumer brand, if you’re at a stage where your product is available for people to buy, I think you should absolutely do everything in your power to try and get your 15 minutes on TV.

Aravinda: Are you still riding on the success of that?

Jyoti: It doesn’t sustain in the way, it becomes 100x in the first month, right? And then it slows to 50-60x, but that 5-6x would have taken you that long to get there on your own. Honestly, it’s hard to quantify everything that comes your way. Sales are one way to quantify, but just the number of opportunities that come up… brands like Zepto, Blinkit, and other e-commerce platforms. If I were nobody, which I was before Shark Tank, it would be much harder to get into closed-door conversations like that. And platforms like that, just access becomes a lot easier. I’ve been meeting people like Harsh Mariwala, and just being able to pick their brains for even a five-minute conversation, it’s a whole different mindset that it puts you into. You start to think about what’s possible and think of bigger possibilities for yourself, the brand, and what it can do. And, you know, you start to believe in leapfrogging and not just building brick by brick. This was one such milestone for us.

Aravinda: Do you want TeaFit to be seen as a tea brand? One of the things within the industry I hear is that coffee is cool; tea hasn’t been able to crack that and get younger customers. Something like TeaFit would, I imagine, interest younger people. So how does TeaFit fit into the larger developments shaping Indian tea?

Joyti: So we feel like there’s a ton of scope to make tea cool, and tea associated with the elderly is, I think, an idea of yesterday purely because it has not been presented in the way with the amount of cool as that coffee does. As a tea-drinking country, I feel like there is an absolutely wide open gap to create a brand that is intentional that is responsible that is cool that is that aligns with the value systems of the young buyer today, and we absolutely consider ourselves to be a tea band before you know any other brands so There’s a lot of innovation that we are currently working on, to innovate on different products and incorporate tea in it. Maybe chocolates. We are working on not just a vertical extension of the product but also taking it horizontally and seeing what else we can do with tea and what other products we can incorporate tea into. I feel like we are at a stage where discerning young people want more than traditional cola/ energy drinks. You do see a lot of experimentation in the cocktail space, in the cocktail/mocktail space, the party space, so to speak. I feel like no innovation has happened in the tea and RTD beverages. So we’re glad to be going after that space and building a brand that resonates with the youth and hopefully makes tea drinking as cool as coffee.

*Ziddii: Adjective. Headstrong, stubborn, obstinate, intractable, adamant, obdurate, intractable. Rekhta Dictionary