Eva Lee is a pioneer of modern tea cultivation in Hawaii, establishing with her husband, Chiu Leong, a tea garden and nursery in the Village of Volcano. The farm supplied growers with hearty cultivars first introduced in 2000 by researchers at the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. Hawaiian tea is grown on many farms producing less than 100 kilos a year. Small amounts of premium tea are exported, but most is purchased by local restaurants and tourists. In this conversation, Lee describes how Hawaii’s “modest but very strong tea industry” adapted during a difficult year.

Uniquely Hawaiian

Eva Lee and Chiu Leong came to tea with a background in the arts, creating an estate within the temperate rainforest near the summit of Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano. The couple are involved daily in every aspect of the farm production including managing a nursery propagating tea, tea processing, conducting tea tours and educational workshops and marketing home grown tea. During the pandemic they added co-packaging and labeling to their set of skills. Lee says that Hawaii has a “significant role in furthering tea culture.” The willingness of the Hawaiian tea community to collaborate with fellow growers, with the support of institutions and researchers has enabled Tea Hawaii & Company to express teas unique to the world, says Lee.

Dan Bolton: Eva, will you update listeners on this year’s harvest?

Eva Lee: Our spring season began quite late, the reason is Hawaii has been inundated with a very, very extensive rainy season we’re coming off of about seven plus months of pretty much straight rain resulting in deep, deep saturation.

The plants have really responded as spring is now revealed itself. The tea plants throughout the state are expressing themselves considerably more this time of year than they have in the past. Usually we would have begun harvesting in February or March for our first flush spring harvest. Right now we have quite a bit of production of harvests going on.

Dan: What makes Hawaii-grown tea special?

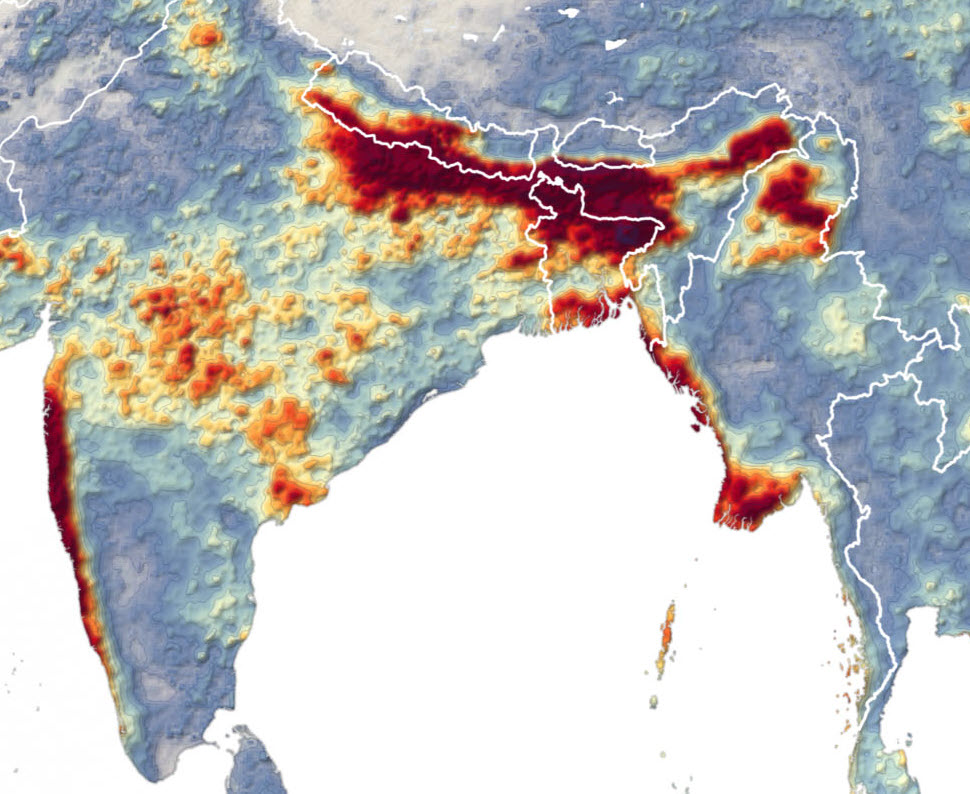

Some of the teas are grown in the native forests. We’ve got shade-grown tea up at 4,000-foot elevations and we also have teas that are in full sun, at 900-foot elevations on the East side of the island.

Our particular garden on the summit of Kilauea Volcano at 4,000-foot elevation is on the windward side of the volcano. A fellow grower on the Leeward side, same elevation, experienced conditions that are quite different. It’s much drier, much more sun. They also had a late spring harvest but here the microclimates, the conditions on the mountain, can be quite considerably different, just moments away.

One of the reasons why the tea is so special is that this generation of tea growers are first generation tea growers. We haven’t had a history of tea agriculture in this state, everyone that is growing tea is doing a lot of experimenting. They are growing it out of a love of the leaf.

Those of us that established ourselves in the areas that are most conducive to tea cultivation have a mulch and forest canopy built over hundreds of years.

In Hawaii, we don’t have the same plant diseases and the same problems or challenges that other tea producing countries have because we are isolated in the middle of the Pacific. We also don’t have continents that are close by, so we don’t have fall-out and pollutants. Every season has a kind of excitement. This year was unusually wet. Each season is quite different. It’s very, very exciting now that we’re at that place where growers here can provide the public with a variety of teas.

Dan: Will you describe the economics of tea in 2021 and how Hawaiian growers adapted to the sharp decline in the tourist and restaurant business?

Here in Hawaii we rely a lot on agritourism. Many of the restaurants here in Hawaii closed down due to the pandemic.

We had to very act quite quickly on decisions as to production. We had to slow gardens down because we were faced with inventory that was not moving because of restaurant closures.

Labor costs in Hawaii have always been much more than in other tea producing countries, so decisions that we had to make definitely hurt some labor because we were not able to have as many people work at the gardens at the same time.

We changed some of the harvest techniques and processing and how much time that we would put into or not some of our crafted teas. So the percentages changed from premium grades to secondary grades.

Our first thought was maybe they’re not as good, but actuality we were nicely surprised that we were able to produce some very wonderful secondary and third grade teas. Instead of selling direct to restaurants, it would go direct to consumers, for instance in food hubs, so we always did a lot of distribution of our teas direct to consumers, in farmer’s markets, but many of the farmers markets were closed down during that time.

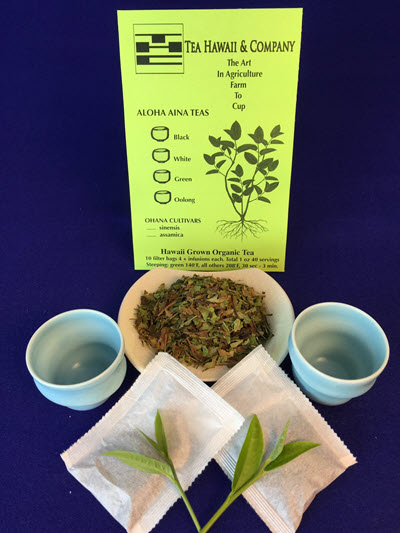

So we ended up manufacturing teas that we called “Tea to Go” for people that were here locally to take our tea and be able to steep them very easily. We were moving from bulk loose leaf to individually filter packing our tea and doing it all here in Hawaii.

We’ve turned into not only growers, and producers, but also co-packers, and so our co-packing activities are also on location.

In Hawaii we have a modest but very strong tea industry. and now some of the people that ended up experiencing the teas found that they were more accessible. Well for premium teas, by the kilo, we were talking about $400.

We are wholesaling them by so many units but to break it down for you they are wholesaled for $7.00 for that 1 ounce 10 filter package so to the consumer pays $8.25, I believe, is the markup of some of these stores and food hubs are doing.

So we also have to have discussions with even on some of our premium tea local retailers. So if I sell this to you for $10, you know instead of selling it for $20, think about $18. That’s a formula that seems to work pretty well with some of the retailers.

We also cut down on some of our costs of packaging. We made our own packaging and so that has helped for this period of time. We may continue, you know. We share a little information on the inside of each package so people can learn a little bit more about us and I think it gives people the confidence to maybe try the premiums.

Collaboration Expands Variety

Tea Hawaii & Company partners with other Hawaii tea growers to expand their offering of rare, premium Hawaii grown teas.

Growers include Mike Riley, who produces oolong tea at the Volcano Tea Garden, located at 3,600 feet above sea level in Mauna Loa Estates. His plantings are from cultivars originating in China, Japan, and Taiwan.

“Johnny’s Garden” owned by John and Kathryn Cross, was established in 1993 in Hakalau on the eastern slopes of Mauna Kea adjoining Kaahakini Stream a perennial spring fed river along the Hamakua coast on the island of Hawaii. It is the oldest of Hawaii’s commercial gardens. John grows Rare Makai Black teas.

? Eva Lee

Share this post with your colleagues.

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

Never Miss an Episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts: