Sandip Thapa, the founder of CuppaTrade, an eMarketplace that enables bulk growers to sell online, says the newly launched B2B eMarketplace exploits new-age tech, including AI and VR, to offer the expanding segment of small tea growers access to a diverse and global base of tea buyers. not interested in maintaining the status quo, “the old way of doing business needs an overhaul,” he says, adding, “We want to blow up the market basically, and to bring in efficiency, make trade much faster, make it extremely dynamic and bring the sellers and buyers closer.”

Listen to the Interview

A Fresh Perspective

Sandip Thapa started his career as a tea taster and auctioneer. He later spearheaded India’s first tea eMarketplace – the Jorhat Tea Centre, working with the Tea Board of India.

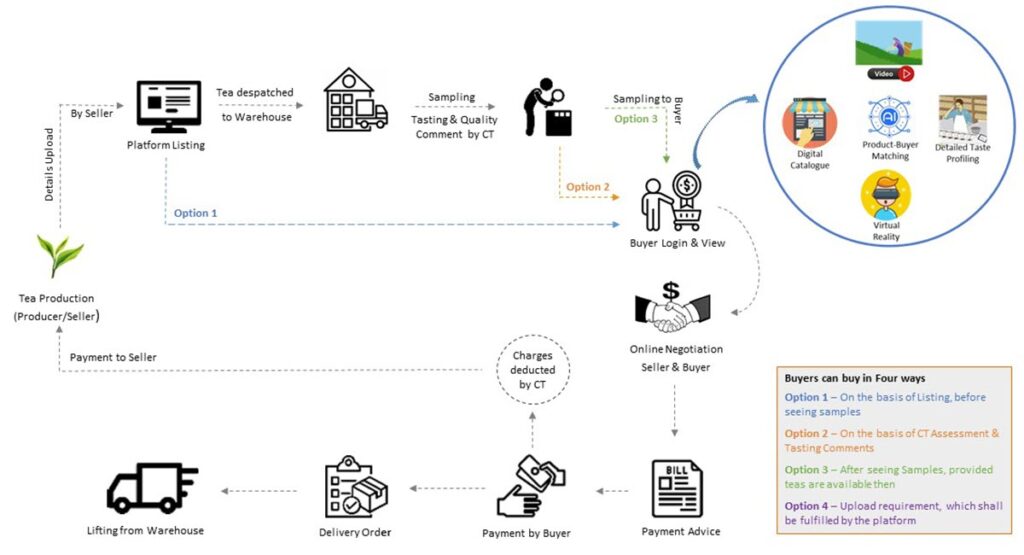

CuppaTrade is a newly launched B2B platform offering the expanding segment of small tea growers access to a diverse and global base of tea buyers. The platform exploits the new-age tech including AI (artificial intelligence) and AR (augmented reality) to connect tea producers across the world directly to buyers worldwide. It facilitates the sale of authentic GI tea to buyers, reducing cycle-time, ensuring quality, providing better renumeration to sellers and making procurement cost-effective for buyers.

In this conversation with South Asia Correspondent Aravinda Anantharaman, Thapa describes a sales cycle that takes far too long, lacks transparency and favors large buyers. Stakeholders shows little interest in innovation. “The need of the hour is a fresh perspective,” he says.

Aravinda Anantharaman: Congratulations on launching CuppaTrade. Will you tell us a little about it?

Sandip Thapa: Thank you. CuppaTrade is an online marketplace catering to the tea ecosystem. We are focusing on the small tea growers’ cooperatives, the bought leaf factories, and the small producers. And we are increasing their buyer base. We are working on their market expansion, and we are going to the secondary and the tertiary buyers. We are connecting the small producers with a very large number of small buyers across the country. This is the plan in phase one, and in phase two we intend to open up for cross-border transactions as well, wherein we focus on the exports.

We want to blow up the market basically, and to bring in efficiency, make trade much faster, make it extremely dynamic and bring the sellers and buyers closer.

Aravinda: Looking at the Indian auction system, where did you feel there are gaps that needed to be plugged?

Sandip: The entire process should have evolved. It is almost 180 years old and by this time everyone knows how tea is to be treated. So, the quality assessment is set, the pre-sale and the post-sale processes are set. What are the responsibilities of the seller? What are the responsibilities of the buyers? These are set and on the basis of these conventions, you see a lot of comfort in private sales. Wherein, the seller is sending samples directly from the garden; the seller is taking the onus of taking care of the quality and the buyer is taking the responsibility of timely payment or whatever the understanding is, with regards to paying prompts or credit terms.

What we should have done is, in the auction system, we should have gone many years ago directly to ex-garden sales.

Technology has yet to play a pivotal role in the ecosystem. So if it’s a broking house or an auction organizer, they could have come up with an app or platform wherein directly from the garden, the tea invoices for sale, could be uploaded and by the time it’s come to the warehouse, your kuchcha or the provisional catalog would be ready. They could have reduced the cycle time. And this is very easy. These are very common sense interventions. Nobody’s doing it, so we might as well do it through CuppaTrade.

Now, we have knowledge in the palm of our hands. Why can’t trade be that quick? You have the learnings of the marketplaces like, Amazon and Flipkart. Unfortunately the tea industry has been bereft of these innovations. You have pockets of innovation, but they’re very tiny. You have progressive sellers and buyers, that’s why you’ve seen the plethora of D2C brands coming in directly trying to sell from the gardens.

So for us, the number one concern is the pace of transaction.

Second is opening up of the market or the platform to add a very large number of buyers and sellers and to showcase small tea growers and producers because the kind of teas they are producing, although the volume is very small, has limited representation.

Next you have to consider credit facility, with regards to receiving the material and making the payment, already set.

It is a Tea Board run auction. The banks and fin-tech companies, could have easily opened up credit facility to the buyers or even to the sellers through the platform. That takes care of the working capital concern.

Finally, I feel it’s very restrictive in the sense that it’s not enough to have a tea board license if you are a buyer. Even if you have a license, you probably will not be able to operate out of any auction center if the committee doesn’t allow it.

So the Buyers Committee is almost like a club. New buyers do get added in the auction system, but if you dig deeper, who are these new buyers? It’s the same old firms registering their new firm. So that is how the new buyers are coming in the platform. But it’s the same handful of 20, 30, 35 buyers. So these things should have evolved. Who should have anchored these? It could be the auction organizer, CTTA (Calcutta Tea Traders Association) or the GTAC, or STAC. It could be the Tea Board, it could be the brokers. But unfortunately, because the industry is so old, you have various interest groups and they run in their own direction. They have their own agenda, they have their own interests to fulfill, and that is how you see where the industry is at the moment.

“The only segment that has made headway are the traders, packeteers, and merchant exporters. They buy low and sell high. That premium never returns to the small tea grower (STG) or producer (STP).”

– Sandip Thapa

Aravinda: In terms of price discovery and in setting prices, the auction offers the benchmark. How would CuppaTrade do that?

Sandip: It’s very unfortunate because when you have a very limited set of buyers, price discovery will suffer. We respect the buyers version, because they also have their own interest to protect because they are looking for value. And with the commodity prices going up, it’s not just the tea price, you have other various costs which is going up, one has to control cost somewhere. Unfortunately, the producers are at a receiving end, where they don’t have much of a say.

And you have to understand the buyers are mostly either traders or agents or packeteers in the auction system. So the procurement cost has to be low so that they make a larger margin. The platform has not been opened to the secondary or tertiary buyers, no one would want to go there and bring them onboard. Else, then what happens to the primary agents and buyers?

We feel everyone can coexist. A small buyer can become a medium-large buyer. A large buyer can become a very large buyer because, when you look at the FMCG industry, everyone is going rural, everyone is going to tier-two, tier-three cities. Everyone is trying to get into just-in-time to fill the shelves, use technology so that inventory is just right and operational costs are down. Similar things could have happened, but when you have a very limited base, how would you expect a fair price discovery?

Yes, you need discipline and you need to put systems in place. But why can’t teas be bought by international buyers at the same time? You have to have mechanisms in place. And it may not be suitable for all kinds of tea. That’s all right. But even on an experiment basis the platform should have been opened up. If it’s a very high quality tea, anyway it’s going to Europe, why can’t the importers be asked to be part of the platform. With a click, you would have expanded the market. And it would be all digital. You log in, explore the catalogue and you bid. How difficult can it be? And now we have working examples, it’s not that we are reinventing the wheel. It’s been many years that Amazon and Flipkart have been in our lives.

If we don’t focus on an alternate, wherein we are speeding up the cycle time, we are reducing the inventory turn-around or providing easy credit in a transparent and open manner from the platform, then when?

Even for that matter sampling. If you go to a buyer’s place, a fairly large or medium sized buyer, the amount of samples they get, it’s humanly not possible to taste all those teas. In many cases, they know what a garden or a particular mark is making. They know the flushes and they know the quality that would be coming out at any particular point in time. So it’s just the type samples they would see seriously at the start of the season or flush, and occasionally the usual sale samples, that’s about it. They do not have the bandwidth to see all samples, because they’re buying from auctions, they’re buying from private sale, they have 2, 3, 4 local brokers sitting outside the office with the samples pushing for sale.

For certain category, you have to see the sample and then only purchase, definitely. Why not? But not for all categories. If you look at the BLF category or the variety that is mostly bought within a particular price range, that anyway is bought on the basis of touch and feel. No one would make the cups and taste. That category is increasing. So if you do something about it, digitize it or have a data set, that one can refer to, instead of just receiving sample, it would make things easier for both buyer and seller.

Here also, CuppaTrade will be using a lot of tech like digital catalogue to make catalogues a bit more interesting and offer more than an Excel sheet; Augmented Reality so that buyers don’t have to go through physical samples. This will save them a lot of space and time. And with our quality assessment, it’s going to be very interesting. They will be able to buy teas on the go, even if they’re travelling or wherever they may be stationed. Once fully ready, we’ll showcase it and we’ll take feedback from the stakeholders. So far it’s been very, very encouraging.

Aravinda: I would also think it addresses one of the concerns that producers have about how many samples they send. Small producers can’t afford to send so many samples in the hope that they get somebody to taste the tea and set a price for it.

Sandip: Correct. So while we are building the AR module, we have already taken steps to get into focused sampling. The process begins right from registration. It’s very thorough. It’s a two step process, where initially, the buyer just uploads the basic details. Then the team sits with the buyer over a call and captures which grades do they buy, at what levels, what are their preferences and so on. And then we also push or showcase the teas that they’re not purchasing. And that is how we nudge them to try new varieties and steadily expand the market.

You would be surprised and happy to know that while it’s been only about three months that we are active and live, we’ve handled teas from Arunachal, Nagaland, Himachal, Upper Assam and South India. And of all shapes and sizes. It could be a five kilo pack, it could be a two kilo pack, all are welcome; green tea, oolong, orthodox, tippy, non tippy, CTC, many varieties.

When we discuss with buyers who mostly deal in CTC, Bolder Grades, Dust and so on and so forth, we ask them, if they would buy green tea as well, or would they be interested in Arunachal Orthodox or some other varieties? They usually say, “No, we do not deal in these teas.” Then we counter, “You haven’t dealt because you haven’t had a platform where you could be assured of a constant supply. Here is your chance, we are showcasing these variety and sending you a few samples.” We encourage them to test it out with their clients, and tell them that now they have a seasoned partner in CuppaTrade who can offer a smooth supply. So this is how we are expanding or helping the small producers expand the market.

Aravinda: The traditional auction system, especially with the mix of commodity and CTC and Orthodox (ODX) has a very complicated grading system that is very intimidating for any new buyer. Unless they already have a sense of all these finer differences between grades.

Sandip: It’s a very interesting point. We have a plethora of grades and most are not required. We had discussed this with Tea Board earlier. Everyone agrees that we need to reduce the numbers and have only the standard ones like you find in Sri Lanka. But here comes the problem, when you say, a particular grade, let’s say a BOP or a BP, it varies between garden to garden because of the sizing of the grains. And that happens because of quality of mesh in sifters, as it varies between manufacturers. You’d be happy to note that during our quality assessment, we are pointing out the mesh size for each invoice.

This is a foundational work that we have started wherein we are providing as many data points as possible for the comfort of buyers. We are laying this foundation so that slowly, we may do away with the samples altogether. This may sound impossible now, but with technology, this is possible.

We realized early, that after a point, when we have lakhs of buyers in the platform, it’ll not be possible for us to send out samples even if we do focused sampling.

It’s a process. Sellers realize it. Buyers also realize that there are too many grades in the market. We need to reduce it. We are talking to Associations too, because it reduces cost for the seller as it helps in streamlining packaging, and is less confusing for buyers.

Aravinda: With the small tea farmer and the bought leaf factory how do you ensure, because the volumes are so small how do you ensure there’s a sufficient supply of a particular tea, a particular grade, which has already found a buyer and who’d like a, the assurance of a steady, consistent supply

Sandip: For stabilizing the supply chain for a buyer with a particular set of variety, we have a mechanism for requirement matching. We use AI to educate the platform that for a particular buyer, a certain category of tea is suitable. Thus, after a point, when we have enough data, the platform will give us and the buyer suitable recommendation basis her buying history. Then, we shall position the new marks accordingly. This way we are trying to bring some semblance and ensure that the buyers have the required supply.

Aravinda: And I think there’s also the opportunity to take back market insights to producers, or to the factories, to the small tea growers, and say, okay, I have an estimate of how much tea of a certain grade, of a certain kind at a certain price band in demand and sort of establish those sort of conversations also

Sandip: Yes, this is what the market is demanding and perhaps they could tweak manufacturing to stay relevant and take advantage of the prevailing market. We want to rely on data and market feedback for this. We are earnest in developing a robust database and analytics to improve all-round offerings.

The other thing with small growers is that, they are defined by one segment, but within that segment itself, there’s such a huge range, isn’t it? There are those who are producing these uber specialty and extremely fine quality tea, and there are those who are still starting out and figuring out a way around making tea. So how do you then navigate this spectrum of small tea growers?

We have already faced this kind of a dilemma because you have certain bought-leaf factories who are working very closely with smart growers and they’re putting in 70% to 80% fine leaf in manufacturing. But the moment the buyer hears it’s a bought leaf factory, the perception gets colored. It’s a constant education process with them. And we insist that they shouldn’t judge either by the mark or where it’s coming from. They should assess and pay only basis the quality.

It’s a process because the perception of BLF is very strong. It’s a volume game for BLF producers with less regard to quality. But when you come across exceptions, you’ve got to fight for them.

Here, we have an advantage because the buyer set is very large and it’s increasing every day. So I think from the traditional platform point of view, when they are selling through CuppaTrade, the biggest advantage is the market base. There is somebody who’s working hard towards positioning them, and we do get into a bit of confrontation with buyers, and urge them to stick to apple to apple comparison on quality because we know what we have, we know the producers, the team and advisors have gone to the factory, we click pictures, we make videos, and we know some of them are very disciplined producers and the result is in the cup. When you taste you know immediately that these have been manufactured with very finely plucked leaves and they’re different. Some of the invoices are even better than many agency gardens, I must say.

It’s a constant positioning that we have to do. And that is how you set the mark, because it’s not just the seller who’s saying that her tea is good, but the platform too, which is supposed to be unbiased. And because we have a large buyer base, it becomes somewhat easier for us to represent those kind of teas.

Aravinda: CuppaTrade is not just a trading platform, it’s also supports a community where conversations can happen, insights can flow from one to the other. And you facilitate, that direct dialogue.

Sandip: We are not traditional brokers. We are not traders. We don’t want to keep a margin. We are very clear on that. Whatever benefit or the higher price that the seller gets, which the buyer is providing, it has to go directly to the seller. We have a service fee. We charge the sellers, we charge the buyers, but that’s about it. We are pure facilitators providing a platform where everyone is welcome to interact, negotiate in a secure, safe environment, while we take care of quality and payments.

Aravinda: So what is the volume you need of buyers and sellers to make CuppaTrade viable and breakeven?

Sandip: We’re going for all. We’re going for everybody. And it’s because India itself is a very, very large market. If you look at the figures, I think the timing of CuppaTrade is apt.

If you look at the auction versus private sale data, auctions are usually around 45% annually. And there is a constant shift towards private sale. We anticipate that this shift will keep increasing. Within a couple of years it will be a stark 40-60 in favor of private sale. CuppaTrade operates in the private space and we don’t conduct auctions. It’s a marketplace, where buyers and sellers negotiate directly and finalize the price and quantity.

As far as buyers are concerned, internally we have taken a target to have about over a lakh (100,000) of buyers across the country. At the moment, we are somewhere near 500 buyers, and we have not even stepped up because, it’s end season in North India. We are focusing on South Indian producers right now. By late February or early March, we shall go all-out and hasten the onboarding process. It’ll be pedal to the metal, so to say.

We want to go to the hinterlands. We want to go to the destinations, hold buyer-seller meets, do the legwork, also to make the onboarding process as smooth and easy, help them understand our processes, our quality assessment, show the AR version of the sample, gauge their comfort level and tweak accordingly. Again, it’s a process and it’ll take some time and as you know the industry is averse to innovation and tech, we anticipate it’s going to be a long haul. But yes, for us, the figure is over a lakh of buyers on the platform.

Aravinda: How difficult is it to conduct transactions on CuppaTrade? What are buyers and sellers required to do to join the platform?

Sandip: It’s very easy. You go to the website CuppaTrade.com and click Marketplace. You identify whether you are a seller, buyer, or both. And the registration form opens up. Many requirements are not mandatory. It’s left to the seller and buyer. That is the first step of registration. Then the team calls and we get into the detailing bit. So it’s that easy and it’s completely free. We don’t pay to be members of Amazon or buy from Flipkart. So that’s the model.

Aravinda: And it comes directly the product itself, eventually comes directly from the producer’s side, the seller’s side?

Sandip: Yes, fresh and in the shortest possible time. We’re removing many layers of traders or intermediaries. In most cases, it’ll be between seller to destination buyer. For certain categories it could be the intermediaries who would be feeding the destination. We are not averse to, agents or traders being in the platform because we are focusing on the ecosystem. Where we bring advantage for both seller and buyer is better remuneration, a large variety in the shortest possible time on a one-stop shop platform with tech driven value-adds. There’ll be many segments of buyers who will be very interested in the platform.

- Related: Turn Over a New Leaf by Sandip Thapa

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.