The defiant American colonists in December 1773 who cheered the destruction of tea in Boston Harbor by 150 patriots in disguise were witnesses to history. The loss infuriated Parliament, which passed the punitive Coercive Acts of 1774, closing Boston Harbor and repealing Massachusetts’s colonial charter until the cost of the tea was reimbursed. Known as the “Intolerable Acts,” these measures convinced colonists to take up arms, leading to the deadly confrontation at Lexington and Concord, New Hampshire, that began the American Revolution in April 1775.

The year-long commemoration of the Boston Tea Party counts down to a grand-scale live reenactment on December 16 with special exhibits and artwork, virtual presentations and webinars, theatrical performances, and the dumping of a thousand pounds of loose-leaf tea (no tea bags) donated to the Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum.

Listen to the interview.

Mighty East India Company

By Dan Bolton

Bruce Richardson, “The Tea Maestro,” has shared his love for tea with the world for 30 years. Bruce, a classical musician and baritone soloist from the state of Kentucky, said that in 1995, he “put down my baton and picked up a cup of tea to travel the world.” His son now operates the importing and blending company that he founded.

“So now I’m probably best known as the roving ambassador for Elmwood Inn Fine Teas,” he said. Bruce has written hundreds of articles and authored and co-authored 14 books, including “The New Tea Companion” with Jane Pettigrew and A Social History of Tea: Tea’s Influence on Commerce, Culture, and Civility. He is an authority on tea culture who speaks frequently in public and is widely quoted in the national press and television. He has served as tea historian and Tea Master for the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum since 2011. Who better to recount the momentous decision to defy the British King and Parliament by tossing 340 chests into the sea, lighting the fuse of rebellion 250 years past?

“When we talk about the Boston Tea Party, we want to put it into historical context, what was happening both in Europe and the colonies at that critical point around 1770 until the time of the Tea Party, which was 1773.”

– Bruce Richardson

Dan Bolton: Will you explain tea’s central role in the confrontation between the colonists and the King?

Bruce Richardson: When we talk about the Boston Tea Party, we want to put it into historical context, what was happening both in Europe and the colonies at that critical point around 1770 until the time of the Tea Party, which was 1773.

Many people don’t know that America was just as much in love with the ritual and tea ceremony as their cousins back in London, Bath, or even over in the Netherlands.

The ladies of Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, and South Carolina were enamored by the tea ritual. They had furniture specially made in their living rooms to entertain their friends and have tea. So, this was what got us into trouble.

King George III says, “The ladies of Boston will pay anything for their tea.” He later regretted saying that because he lost one of his greatest colonies over a cup of tea.

In the 1770s, Boston was consuming copious amounts of tea brought in on board merchant ships — and some illegally. The only tea that could be brought in was through the Honorable East India Company, incorporated by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600.

The problem began with the taxes on tea being so high that the price was going up and up. The Dutch saw an opportunity to undercut the East India Company by smuggling tea into the colonies. So, by 1770, the British East India Company was about to go under, and they told Parliament it looked like if “John Company” went under, the government would go under, and the banks would collapse.

“We are a company that’s too big to fail,” they said.

So, Parliament gave them the option of having a clearance sale on the tea piled up in their warehouses in London.

All that tea came from only one country, China; no tea was grown in India then, and there was no tea in Sri Lanka. The Japanese were growing tea, but they weren’t exporting it.

So, all the tea that went into Boston Harbor or the teacups of Jane Austen all came from just one country, China.

The tea was coming into the London warehouses but wasn’t going out fast enough. So, it started to pile up and get old – it had a shelf life. So, Parliament, even though deeply indebted, said it would allow the East India Company to ship 544,000 pounds of tea out of its warehouses to the colonies without paying a tariff.

On September 27, 1773, seven ships started to leave the Port of London on their way to the colonies. Now, they weren’t just going to Boston; they were also going to New York, Philadelphia, and all the way down to Charleston, South Carolina, because these were the major tea-drinking cities of the Americas. So, the ships left and made their way over to the colonies towards the end of the year.

On November 30th, the first ships started arriving in Boston; four ships were sent to Boston – showing you how much tea was being consumed then. One Boston-bound ship, the William, was lost at sea. One ship arrived at each of the other three cities.

Well, Boston pretty much had to make the decision. The other cities said, “Well, Boston, it’s up to you. If you take this tea in, fine. If you don’t, we will follow your lead. Whatever you do, we will follow.”

The Polly landed at Philadephia and was turned around, fully laden, and sent back to London. The same fate awaited the late-arriving Nancy, bound for New York. Charleston seized the cargo of tea and placed it under guard in the Customs House.

See: The Tea Maestro

The tea coming in was actually cheaper than previous shipments because no tariff had to be paid to Parliament. There was, however, a small tax that the government retained on tea to pay for royally appointed governors in the colonies.

And so that’s what was the rub. That was the straw that finally broke the camel’s back.

Once people learned the tea was coming, they got together almost weekly to talk about what would happen with the tea. It all came to a head on December 16 of 1773 in the Old South Meeting House. Thousands of people crammed into that square around that building to decide what to do. They couldn’t make a decision. The ships were sitting in the harbor. Everything had been offloaded except the tea. And finally, Samuel Adams said, “We can do no more.” And that was, we think, the signal for his people he organized to go down and destroy the tea.

And that’s what happened over the next two and a half hours. Tea valued at nearly 10,000 pounds went into Boston Harbor that night. Today, the value would be well over a million dollars.

Witness the 250th Anniversary Reenactment

On December 16, 2023, Boston will commemorate the 250th Anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, a moment that forever changed the course of American history. On this day, the collaborative efforts of multiple organizations will culminate in a grand-scale reenactment of the Boston Tea Party. A full evening of reenactments will play out in 4-parts across the City of Boston at several historic locations.

Dan: Several different teas went overboard that night. Will you describe them?

Bruce: One of the questions I get often is, was that brick tea? We know it wasn’t tea bags, but not brick tea. It was all loose-leaf tea. All the brick tea went the northern route, through Mongolia on camel’s backs and horses, to make its way to Europe. Loose tea came through the East India Company. So that’s what went overboard that night.

It’s interesting that the tea went into the harbor at low tide, maybe two and a half feet. And all that tea started piling up alongside the ships. And men had to go out in rowboats and with their oars to knock haystacks of tea down to get it into the water to be destroyed.

When I talk to audiences anywhere, they are always fascinated to know this tea comes from only one country, China, but also that of the five teas tossed overboard. Two of them were green teas. And three of them were black teas.

The major portion of the 340 chests, and when we say chest, we mean a large wooden case that held this tea, often lined with moisture out. The chests could weigh anywhere up to nearly 250 pounds. So those all had to be hoisted up out of the ship’s hold and broken open to destroy them.

They held five different teas; we know what they were because the East India Company assembled an invoice over the next few months listing all the different teas by category, how much each weighed, and how much value they all had because they wanted reimbursement. So, the main portion was bohea, a black tea from the Wuyi mountains. The other black tea was Congou, a very well-made black tea, and then the third one was Souchong (today we know as Lapsang Souchong and then the two green teas were Hyson green tea and Singlo from the Sunglo mountains of Fujian Province.

Dan: The Tea Act allowed the East India Company to sell tea directly to loyalists, cutting out colonial merchants and leading to a boycott of tea. Destroying the tea cost the British government, but local merchants in all the colonies also lost significant revenue because drinking tea was suddenly unpatriotic – only loyalists drank it.

Bruce: The arrangements through Parliament, through the East India Company, to go through the people who were loyal to the King. These were all loyalist merchants who would receive this tea; it wasn’t just the common everyday merchant down the street. And that, again, was another thing that rubbed colonists the wrong way.

Bruce: It wasn’t patriotic to drink tea after the 1773 event, but even leading up to that, people got together and signed letters saying they would no longer drink East India Company tea. This caused a problem because they still had all the tea-making apparatus. They still had beautiful teapots and teacups. And the ladies of Boston wanted their tea times. So, they went out into their gardens and orchards to find whatever they could to go into those teapots to make something colored water they could serve. So, you had a great advance in people drinking herbal or fruit teas at that time. They called their teapots Liberty teapots. These teas were called Liberty teas because they contained none of the tea that George III consigned.

They were making a statement about not drinking Chinese tea anymore.

Dan: None of this tea was shipped directly from China to the United States; it was sent to London, weighed, taxed, and stored before sailing six weeks across the Atlantic. This meant the tea was never as fresh as tea shipped directly to the colonies by the Dutch.

Bruce: There was never a direct shipment of tea from China to the Americas until the first January after the United States was formed. The very first ship, the Empress of China, that left the port of New York bearing a flag of the new United States, traveled to Canton, loaded with all the American black ginseng they could find in the colonies. And guess what they traded it for? They traded it for tea. And so a huge amount of money was made on that very first shipment of tea back to the United States.

Dan: It turns out there was a huge market for the 242 casks of New England and Appalachian ginseng. American ginseng was so popular in China that that continued for decades.

Bruce: Indeed, the Chinese could never get enough ginseng. They were delighted to have it. And, by the way, they said, you can take all this tea back with you.

Dan: Let’s flash forward. This is a delightful opportunity, a first glimpse or prelude to the nation’s 250th anniversary. In two weeks, everyone in Boston will turn out to watch the reenactment. The Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum has been collecting tea from donors to toss overboard. Will you share some exciting things that will make this a fun and authentic celebration with listeners?

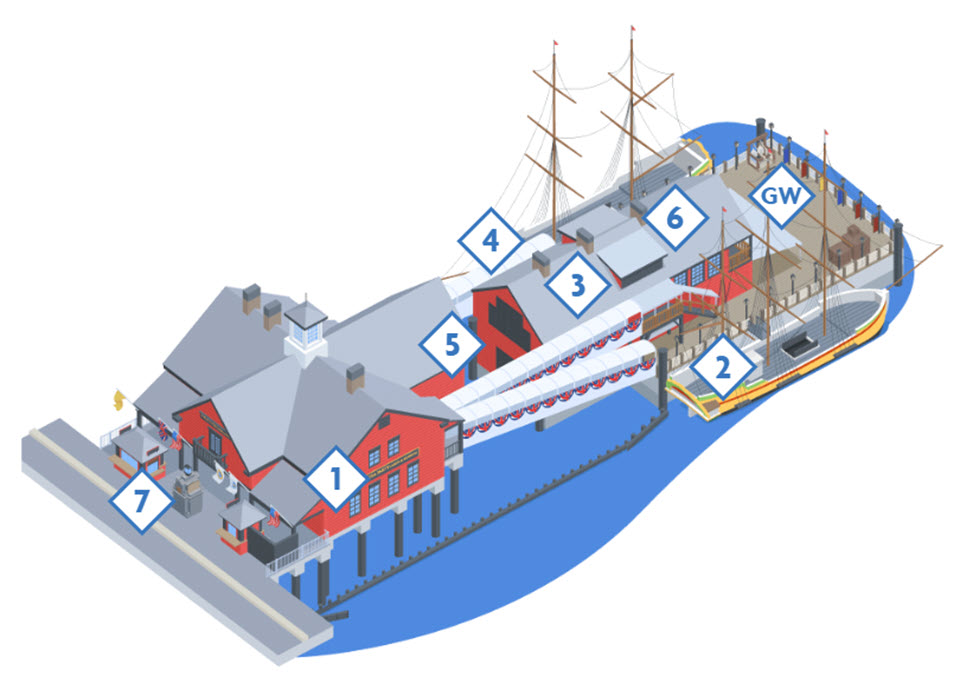

Bruce: The Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum started a dozen years ago because the mayor asked, “What’s the most iconic event in our history… And we don’t have a museum to interpret that?”

Even before they poured the first concrete, they came to me to say they wanted to get the story right. We want to know what the origin of the tea was. We think that’s important for our museum.

So, I’ve been with them all those years, and we have the museum there rising out of Boston Harbor. We have two ships that are replicas of the ships that were there in 1773. People can go through an interactive display and immersion into the days of the colonists, go into the hold of these ships, and actually see one of the tea chests that was broken open in Boston harbor. We even have a vial of liquid tea made the next morning from some of the tea leaves that washed up on shore. Over two million people have come through the museum and finished drinking tea in Abigail’s tearoom overlooking Boston Harbor, where they can taste the five different teas tossed into the harbor that night.

So, in Boston on December 16 of this year, the entire weekend will have events that will have reenactments of the Old South Meeting House of the discussions going on between the city leaders and the people who were or just adamant about throwing the tea overboard. And then we’ll have Fife and Drum Corps and bands, all leading people in parades down to Boston Harbor.

The Boston Tea Party ships museum will set up viewing stands, and we will re-enact the Boston Tea Party once again, with tea going overboard. We had over 1,000 pounds of tea going into Boston Harbor that night. We have a certificate signed by the cities that says we can put tea into the harbor now because it’s illegal to dump things like that into the harbor. But we’ve got it all taken care of. Tea is highly biodegradable and there are no tea bags. Everything must be biodegradable.

Bruce: Most colonists really didn’t want to separate from England. They just wanted representation if they were going to pay taxes, they wanted to have a representative in parliament that looked after their needs. So it wasn’t until this event, the Boston Tea Party, that the tide started to change, and people like Samuel Adams started to think, well, there’s no going back. We’ve gone too far; we might as well just go ahead and form our own country.

If it had not been for the Boston Tea Party, the separation may have come, but it may have come years later than when it did.

Tour Hours: 10 am – 4 pm

(866) 955-0667 | 306 Congress St.

Boston, Mass.

Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum

Photos courtesy Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum | December16.org

December 16 Boston Tea Party Reenactment

Latest Episodes

Powered by RedCircle

Share this post

Episode 145 | On December 16, 2023, Boston will commemorate the 250th Anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, a moment that forever changed the course of American history. On this day, the collaborative efforts of multiple organizations will culminate in a grand-scale reenactment of the Boston Tea Party. Author and tea historian Bruce Richardson, “The Tea Maestro,” has served as Tea Master for the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum since 2011. A renowned storyteller, Bruce recounts the momentous decision to defy the British King and Parliament by tossing 340 chests of tea into the sea, lighting the fuse of rebellion 250 years past.