Caption: Researchers and members of the London Tea History Association smelling a 172-year-old yak-butter container during a workshop in January 2020. Image used with permission, Andrew McMeekin Photography

In 2019, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew began analyzing the provenance of more than 300 tea specimens of mainly Chinese and Indian grown teas dating to the 1850s. Ethnobotanist Aurora Prehn began by examining labels. She then proceeded to record non-textual evidence experienced through sight, touch, and smell. In this interview she shares her findings and offers some interesting insights into the work of Horticulturalist Robert Fortune whose specimens are included in the collection. Listen as we learn about tea from 1853.

Q|A Aurora Prehn

Aurora Prehn is an ethnobotanist working independently researching the nexus of culture and nature while consulting in areas of expertise under her LLC, People & Plants. She completed her BA in Anthropology and Environmental Studies from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 2013 where her research examined local food culture, health, and the environment. Following graduation she spent five years in the specialty, organic tea and botanical industry at Rishi Tea finishing as a tea taster and educator. In 2019 she completed her MSc in Ethnobotany at the University of Kent and the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew in the United Kingdom.

Dan Bolton: Will you share with our listeners what it’s like to examine tea from 1853.

Aurora Prehn: The collection is quite old, so the leaves are different shades of brown. Of course they’re oxidized but the different shapes expose different tea types. Compression was a major theme that surfaced right away, as well as a whole slew of different Orthodox shaped leaves.

I didn’t touch them directly without gloves, and very rarely, very sparingly to preserve them, but rotated the jars to expose different labels that were hidden and even bits of metal that were stamped labels as well as a little bit of tea chests.

We all know tea absorbs scent. I was shocked to smell white tea and pick up nuances, smelling some greens that are now brown, but you can tell that there’s still that green heart there.

Yak butter has a very interesting, distinct smell, and 175 years old is still a little bit pungent.

And as far as how the collection tastes?

Well, maybe one day if Mark allows, I would love to try some.

Dan: The storied botanist and tea explorer Robert Fortune is part of the narrative. He was not working for Kew, but many specimens that he collected ended up in the museum. Will you briefly describe his adventures.

His story is fascinating.

I read a wonderful biography by Alistair Watt (Robert Fortune: A Plant Hunter in the Orient) that really covers his whole life and career. He’s a horticulturalist by training and is a plant hunter who traveled to Asia, mainly China, on five expeditions between 1843 and 1861.

Fortune was hired by the Horticultural Society of London and then the East India Company and traveled on behalf of the US government. He also collected insects and different antiquities and wrote extensively about his work in the Gardeners Chronicle as well as the Journal of the Horticultural Society of London.

He also wrote five books on his expeditions with a map of the tea lands which shows what was believed at the time. It doesn’t show the experimental test plots in Darjeeling or in South India and the area of Assam that we know that grows tea. We know that Korea has been growing tea for hundreds of years and was left off the map so it’s really quite interesting.

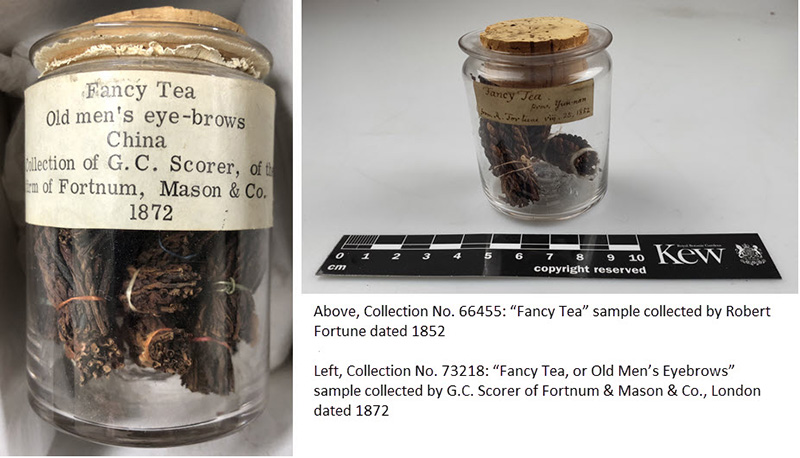

We have two artifacts in the collection from Fortune. One is a set of 24 paintings showing how tea is grown and processed on paper that was requested by the collection’s founder. William Jackson was writing about the plant used to make that paper, so I think the paper itself was slightly more of interest than the depictions.

The second was this fancy or twisted tea that was collected in 1852. It came from Yunnan, where Fortune wasn’t traveling, so it was likely he collected from a port.

Dan: Kew hosted multiple workshops in January 2020 for members of the tea community from the UK and Ireland – prior to closing the gardens during the pandemic. Aurora, how can listeners learn more about this marvelous collection?

Aurora: One way that people can engage this collection is through the online catalog available on Kew’s website. Search economic botany collection by just typing camellia.

One of the really remarkable things about this collection is how intact it is. Teas that were identified in the 1850s, they’re still here and still intact.

This is what’s pushing me to keep going remotely during this pandemic, because I know that listeners and tea nerds around the world are really just going to love it. There’s going to be even more coming out of this project.

Rediscovering 174 Years of Tea, Chai, and ?

By Aurora Prehn and Mark Nesbitt

There are many histories of tea’s material culture, each depending on the perspective of the historian and, crucially, the raw material and methodology of analysis. This collection is distinct from those of most other museums and archives in being composed primarily of tea leaves, rather than teaware or documents. The majority came from across Asia, between 1847 and 1914, and include all parts of the tea plant, from root to seed, as well as clay, other woods, bamboo, and metals. Alongside processed tea leaves from all six tea categories, the collection also contains: seed husk and flower bud cakes, rare tea types, bricks from remote trading outposts, wooden statues, teapots, adulterated tea, fermented lappet, extracts, and a single yak butter container with an aromatic note left from its contents approximately 172 years ago. As one can imagine, these artifacts contain many biocultural stories, histories, and perspectives.

Share this post with your colleagues (copy from post block at right)

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts: