The tea sector in Bangladesh is expected to return to near pre-pandemic production levels after setbacks in 2020. Like neighboring Assam, Bangladesh experienced a spring drought, high temperatures, aggressive pests and the onslaught of the pandemic. Despite these challenges production through July is ahead of last year’s totals and estimated to reach 86 million kilos.

Caption: A monument known as the Tea Daughter at the entrance of Moulvibazar district at Srimangal, Bangladesh. Photo courtesy Faizi Tea Estate, credit: Shomoyeralo.com

Tea Gardens Benefited from Timely Government Actions

By Dan Bolton

Mohammad Musa, manager at Finlay Tea’s Consolidated Tea Plantations in Habigonj, and Moulvibazar, Bangladesh, writes that “Plantation work never stopped during the Pandemic. Workers were kept isolated in the tea estates itself and there were many more safety programs. Government support was encouraging, which really enabled plantations to continue running of the tea estates activities safely during the pandemic.”

Cyrus Anushirvan Faizi, Executive Director at Faizi Tea Estate, reports that the first seven months of the year brought favorable weather.

“Tea production has been consistently increasing thanks to the favorable weather and initiatives undertaken by the [Bangladesh] Tea Board,” he writes. “The distribution of fertilizer at subsidized prices started in the gardens at the right time this year,” Faizi explains.

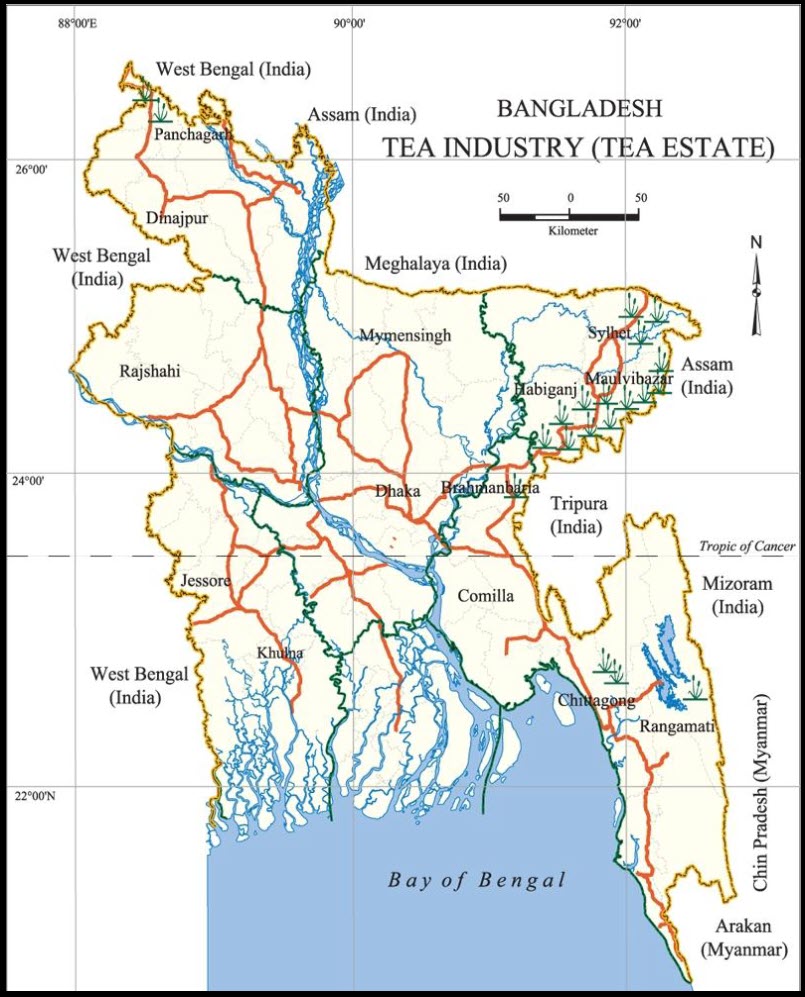

In spite of the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, data from the Bangladesh Tea Board shows the nation’s 167 large and small tea gardens produced 86.4 million kg of tea last year, exceeding the 75.9 million kg targeted. During the past 10 years annual production has increased from 60 million kilos to a 166-year record of 96 million kilos in 2019.

The International Tea Committee in London ranks Bangladesh 9th among the tea producing countries. The industry employs 100,000 permanent workers and 30,000 casual workers. There are approximately 5,000 small holders producing tea. Exports by value fell 5.7% to $3.2 million, according to World’s Top Exports which reports International Trade Center data.

Early this year the Bangladesh Tea Board projected tea production will reach 77.8 million kilos. Halfway through the harvest year growers are optimistic they will exceed that total. “About 51% of the target has already been produced in the first seven months,” writes Faizi.

In 2020 production was greatly hampered due to the pandemic, a severe drought and insect attacks. A nationwide lockdown was imposed by the government in March 2020 to curb the spread of COVID-19 resulting in a drop in crowds in hotels, restaurants, and tea shops as well as a precipitous decline in tea sales.

“However, even during the pandemic, the tea estates were fully staffed and running smoothly which helped the industry to meet its production target,” writes Faizi.

“Plantations are mostly in isolated from the city or localities,” explains Musa who oversees 8000 hectares of tea producing 12 million kilos annually. “Workers were kept isolated in the tea estates itself and there were many successful safety programs against the COVID at the tea estates. Plantation management arranged harvesting on daily basis by observing all safety measures for the workers against the COVID and continue to make sure that workers wear masks, wash hands before and after starting the work,” he writes. Safe distances were enforced during leaf weighing and in the factories all sorts of safety precautions were strictly maintained and continued manufacturing of tea, writes Musa.

Musa writes that “logistic and supplies were interrupted during the pandemic though the plantation management somehow managed timely payments for the workers. Tea plantation really faced acute difficulties about the materials for the estates day-to-day activates.”

Tea production was also hampered by unfavorable weather and insect attacks during the first five months of the 2021, resulting in a 10% decrease compared to the previous year.

Musa writes that “one of the main adversities is drought. During the past couple of years tea plantations in Bangladesh experienced the equivalent of six months of rain less days every year.”

“This tropical region climate is already hot, sometimes it goes beyond tolerance for the tea bushes,” he explains. “To tackle this situation most plantations in Bangladesh are using shade trees to block at least 40% of sunlight over the tea bushes. During the drought plantations used irrigation systems ( mostly overhead sprinkler irrigation systems of various sizes). These irrigation sets were mostly used with the perennial water. Plantations also use mulching to reduce evaporation of water from the soil. Some are using subsoil watering to minimize damage,” writes Musa.

Tea producers in Bangladesh are now at a crossroads, according to Faizi. Improving their marketing performance in both the domestic and export markets has become crucial for survival and growth, he writes.

“Old saplings have been removed and new saplings have been planted. The tea planters have increased the scope of tea cultivation by making new investments,” writes Faizi, adding “If the trend of increasing production continues like this time, then there will be no need to import tea in large quantities.”

“The tea sector has lost its name and fame in recent years, but in light of such challenges, strategies have been adopted in the coming year to meet the demand for tea in the domestic as well as global market.”

— Cyrus Anushirvan Faizi

Faizi Tea Estate

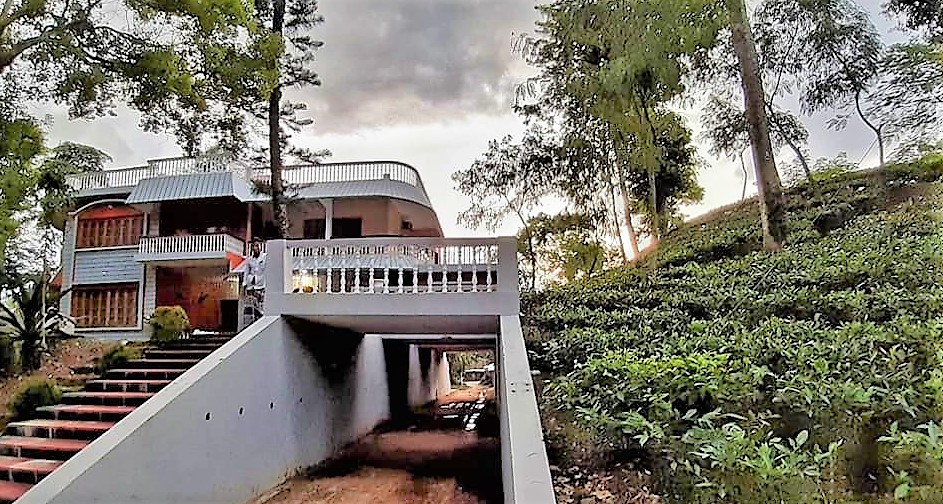

Tea was first sowed in 2015 at the Faizi Tea Estate in Kulaura, a small village in Moulvibazar District in Sylhet, not far from where the first commercial tea garden was established in 1855 at Malinchhara Tea Estate.

Faizi, the garden’s executive director, is a lawyer and consultant with a degree from the University of London. He writes that “tea is a potential export product of the country with high demand abroad. There’s a lot that can be done for the development of the tea industry and the welfare of tea workers. The production will increase if the necessary support is provided, exchanging views with entrepreneurs in the tea industry.”

Faizi explains that “the tea industry has undergone a number of changes in the last decade. The government and tea planters have taken a number of steps to achieve record production in tea (2019). The government announced a roadmap in 2016 for the development of the tea sector, setting a production target of 140 million kilos annually by 2025.”

He writes that “The tea industry is currently making a significant contribution to the country’s economy through export earnings, contributing to a trade balance as well as generating employment. New tea estates have been established in new areas where the climate is suitable for tea plantations. Large corporate groups have begun investing in tea plantations in response to the rise in consumer demand. Bringing large corporate groups into tea farming is helping to increase production, as well as introducing more knowledge and technology. “

— Dan Bolton

Bangladesh is famous for its Seven Layered Tea also known as Seven Colored Tea. The recipe is a secret. Every year tourists visit the city of Srimangal in Moulvibazar just to taste this tea paying from 70 to 100 Taka ($1) a glass.

Resources

Share this post with your colleagues.

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

Never Miss an Episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts: