Recirculating heated exhaust conserves energy and helps to eliminate inconsistencies in drying that lower tea quality. In this installment of Frugal Innovations, Ranjit Chaliha describes Varun, a device named after the Hindu God of Wind that continuously monitors ambient air conditions in real-time and electronically computes the ideal inlet air temperature to reduce energy costs enough to pay for itself.

Hear the interview

Achieving Consistency and Efficiency in Drying Tea

By Aravinda Anantharaman

In 1961, Ranjit Chaliha arrived at his family’s Korangani Tea Estate in Assam. And never left. He had trained as a mechanical engineer and worked briefly at the Assam Electricity Board. And now, the tea factory became a place of many experiments. He eagerly adopted new technologies and tinkered with new machines. Chaliha also became a member, and later, chairman, of the engineering subcommittee of India’s Tea Research Association, involved in machinery development and tea research. It was during his tenure that the Model Tea Factory in Tocklai was constructed. Chaliha began experimenting with methods of recirculating exhaust in the factory’s tea dryers. At an engineering symposium on tea machinery in 1998, he presented a paper describing the benefits of recirculating exhaust air. He based his findings on experiments and filed for a patent. A dozen years later he was finally awarded recognition for his innovation, Varun, a device that reduces inconsistencies in drying tea.

Aravinda Anantharaman: Congratulations on the patents Mr. Chaliha! How long did the patent take?

Ranjit Chaliha: For me, it took 12 years. And unfortunately, the patent examiner initially was not convinced. He was not impressed. He put all sorts of other irrelevant questions and things like that. Ultimately, it came out as a very pleasant surprise.

Aravinda: So how did the idea for Varun come about? What does it do?

Ranjit: In the tea dryer, ambient air is heated to a high temperature – about 200 degrees Fahrenheit and blown through tea leaves thinly spread on perforated trays. The air goes from below the trays through the tea and up.

In Assam, weather changes from dry at the beginning of the year to very moist during the monsoons and again dry towards the end of the year. July, August, and September are moist months. The air is also heated to 200 degrees Fahrenheit and blown through the wet tea leaves until they get an acceptable result. But come November, when the atmosphere itself is dry, the air itself is dry, and this air is heated to the same 200 degrees Fahrenheit. In July, the ambient air would have a relative humidity of, let’s say, 50% to 60% or maybe more. In November, the relative humidity is maybe 30% to 40%, and it is heated at the same temperature. Instead of 4% to 5%, the relative humidity would go down to probably 2% to 3%, which you don’t need. Not only don’t you need it, it’s bad because the air becomes drier than before and you get a faster drying which is also not good. So, I thought to myself, why heat till 200 degrees?

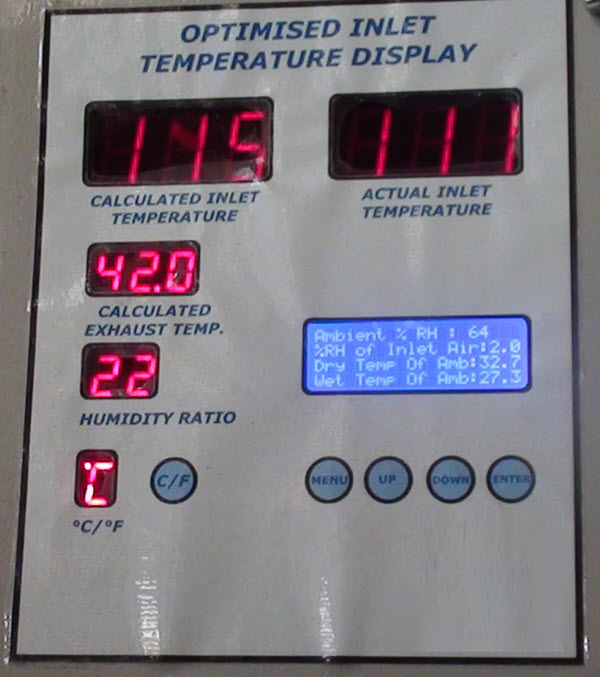

Why not till about 190 degrees, or 180 degrees, so the relative humidity goes down to nearly what it was in July. So that was the beginning of my thought process. Then, a lot of studying and a lot of maths and things are involved in implementing the idea of making a monitor, which would tell you that this is the temperature you should dry the air to get a relatively consistent drying. I teamed up with an electronics instrument equipment manufacturer in Kolkata. I gave them the know-how, and they built this instrument. It was very good. But except for two or three gardens, people didn’t accept it. The inlet temperature must be input manually, which they didn’t want to do. They wanted it automatic. At that time, I didn’t want to invest so much money or time; the patent had also not come. So, I left it at that, but those who took the instruments were reasonably happy. But now that the patent has come and my two sons said ‘dad, we have got to have another try.’

“Tea quality is impacted by numerous things, including the drying rate. If the tea is drying too fast, some quality will be lost. And if it is dried too slow then also quality will be lost.”

– Ranjit Chaliha

Aravinda: How does monitoring the temperature and controlling the drying impact the tea itself?

Ranjit: It would be best if you got more consistent drying. The quality of tea is impacted by numerous things, including the drying rate. A drying rate of 2.8% to 3.6% moisture loss per minute is preferred. If the tea is drying faster, some quality will be lost. And if it is dried slower than that, then also quality will be lost. So, there’s a range within which the leaf drying rate of the tea should take place. This is dependent on things such as the temperature it’s heated to and the relative humidity of the hot air. That is also dependent on the ambient conditions of the air to start. Since the ambient conditions vary, the hot air conditions will also vary if you heat to the same temperature. This instrument will tell you that to keep a reasonable consistency in the condition of the drying air, to what temperature the leaves should be heated.

Aravinda: Who is this monitor most helpful for? Is it for CTC or Orthodox? Can anyone use it?

Ranjit: Yes, yes, of course, it’s got to be calibrated differently for different ways of manufacturing, different machines, different sources of heat, and mainly different dryers. Also for situations, locations… It’s a psychrometric thing. So it’s got to be adjusted for height above sea level.

Aravinda: And how difficult or easy is it to install and implement it?

Ranjit: Very easy. There’s just a meter with leads. It’s nothing complicated.

Aravinda: How quickly can a producer get a return on investment?

Ranjit: Within one year.

Aravinda: Well, that’s not a long time at all. Compared to, say, 12 years for the patent. What are your plans to go to market?

Ranjit: Firstly, it’s an uphill task. People have tried to sell this instrument in the market earlier. As I said, only two or three were sold. Now that we have got the feedback that they are not interested in doing manually we know that we have to make it automatic. There are different ways gardens heat the air; gas in upper Assam with the rest of the regions using coal. With gas, it’s easier. You have a connection with the burner, and you can regulate it with the burner. With coal, some more work has to be done. But first, let me get this manually operated machine going. Also, I have to say this, it’s not a glamorous thing. It will give you savings in fuel, maybe up to 3%, and consistency in drying. A 3% savings for a big factory making 1 million kilos is INRs6-7 per kilo. Even a savings of 2% is much more than the cost of the instrument.

Frugal Innovation

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.