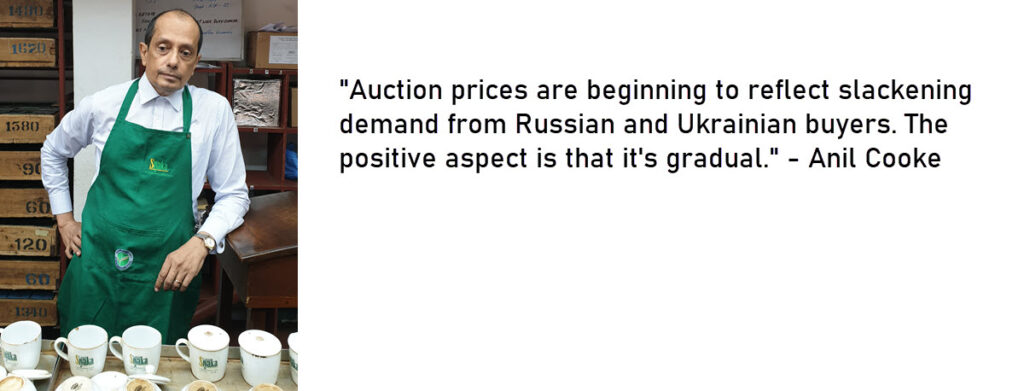

Sri Lanka is facing its worst economic crisis since gaining independence. Following the pandemic, many industries on the island ceased to exist due to political and financial difficulties. However, the island’s tea industry continues to battle on. Tea Biz correspondent and PMD Tea MD Dananjaya Silva discusses with Dr. Roshan Rajadurai, the Managing Director of Hayleys’ plantations how Hayleys’ plantations have adapted and continue to produce tea, given the economic hardships.

Caption: Dr. Roshan Rajadurai, the Managing Director of Hayleys Plantations, left, discusses with Tea Biz correspondent and PMD Tea MD Dananjaya Silva how organizational discipline and adaptations enabled tea production to continue during the pandemic and recent economic hardships.

Listen to the Interview

How Sri Lanka’s Tea Industry is Coping with Continual Crisis

By Dananjaya Silva | PMD Tea

Production is down and export volume declined compared to last year but auction prices are at a high mark and Ceylon tea remains in demand. I traveled to Sri Lanka to assess the condition of a resilient tea industry following an unsettling spring marred by high unemployment in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic. For several months tens of thousands protested the inflation-driven cost of food and shortages of basics, including fuel, cooking gas, and electrical power. The upheaval led to the resignations of both the prime minister in May and the nation’s president, who fled the country in July.

Dananjaya Silva – How did the COVID pandemic restrictions show Sri Lanka’s plantation sector to be resilient and adaptive?

Roshan Rajadurai – The plantation sector has a legacy of 150 years of very well-organized, centralized management structure, so when this pandemic situation suddenly came up the government imposed a three-day curfew which we had to abide by. But on the fourth day onwards, we quickly got on board, and made things as normal as normal could be.

The moment we caught wind of this pandemic situation, we put in place a series of measures at our 60 tea and rubber plantations. First, of course, we made our people aware of what this is all about.

There was an influx of people from Colombo and outstations, flowing back to the estates. So, we made sure their names were recorded, and if they showed signs of infection, we had isolation quarters. We isolated them for 14 days, and kept the medical and other authorities informed when they returned to the community. The organized sector has one million people living in a village-style setups in close confines. The measure we took were effective. Up to about the end of last year, we didn’t have a single casualty arising out of COVID. That is because we identified and limited exposure to the people who were coming from outside.

In addition, we did fumigating and provided simple medicines. And most importantly, we ensured that people didn’t have to congregate and that they didn’t have to go to bazaars and townships.

We organized distribution with the large food suppliers, like the government warehouse system, and brought in food in lorries. And we had stocks for two or three months. We delivered food packets practically to their doorstep. What is important is that we ensure that the workers did not spread this COVID.

There was also a group of people who had no other means of earning more income. Although last year was not a good year financially, we ensured that their wages were paid. And as a means of helping the people in this situation, we opened our industry to those who arrived from Colombo and elsewhere, and gave them work in areas that we could not manage with our regular workforce. So, their family unit had more opportunities to earn more when sons and daughters returned.

We already had in place a revenue share model, so we expanded it. There were a lot of people who didn’t want to be registered workers but they still got into the earning pool for their family and were able to enhance their family income.

So we had a very, very tough and a very well disciplined control system and to the credit of workers, I must say they cooperated fully.

They listen to the management; they follow the advice of health departments. So that’s an example of success and how after long years of practice the plantation sector was able to manage a crisis like this.

Dananjaya Silva – How did adaptations forced by the pandemic help Hayleys prepare for the political turmoil of 2022?

Roshan – After COVID came the financial crisis. There was no work to go back to in the construction industry as it had crashed, and also the eateries and small hotels. So, all the people came back to the estates and we made available opportunities for employment. One example is paying workers to remove weeds. We said we will pay you by the kilo and that was a very good intervention as people who don’t want to return to sort of plucking or harvesting work, they go to the field, remove the weeds and we pay them. This was essential because of the limitations on fertilizer. We convert the weeds to compost. Soil augers were given to each division and placement of holes tracked. Once the compost is made, we filled the holes and incorporated the bulk material and the compost into the soil so that it enhances the soil fertility.

Dananjaya – What you’re saying is that this 150-year-old industry, that has been the backbone of the Sri Lanka economy, continues to be that because workers who are from plantation backgrounds who’ve worked in hotels, construction, they once again come back to live on the estate.

Roshan – Actually, Dananjaya employment is only part of the solution that we provided, because there was an influx of workers. And it’s actually stretched our services. But we made sure that we accommodated them, that we looked after them in terms of food supply, because there was no food because the COVID curfew and restrictions. So our managers went out and bought curfew passes, they really did a great job on the ground. I mean, they volunteered – they could have waited and said, look, we don’t want to expose ourselves. But every company, every manager, every planter, took it upon himself to look after his community on the discharge of food, medicine or the wherewithal. Everything was provided and absolutely no breakdown. And ours is the only industry right now maintaining the industry as it was before a lot of challenges, a lot of stress, a lot of issues, but we still maintained the industry as it was.

Dananjaya Silva – Fertilizer was banned last year then the government subsequently reversed the policy. How is this affected Hayleys estates?

Roshan – Well, on the whole, banning of fertilizer was a shock and surprise to all of us due to the ill effect and the consequences of this hasty, unscientific and illogical strategy. We made significant protests, voicing opposition in media and TV talk shows and whatever but to no avail.

We are a large organization and we stock sufficient fertilizer for one or two applications ahead. Last year I did not plan for the banning, but I thought that we learned some lessons on logistical problems, with fewer ships coming, curfews on crews and the slowed movement of goods. So we gave instructions to our managers to store fertilizer for six months, anticipating a breakdown of logistics. Then, in the meantime, they banned the fertilizer, and therefore we had some stocks. Uncertain supply and high prices completely changed the way we apply fertilizer now because we know that for a year or two, we might not get cost effective fertilizer.

In the past we used to broadcast fertilizer but we quickly reverted to a system called placement where we dig a hole and put in a measured 24 grams of fertilizer per bush. In this way, you’re reducing the wastage from volatilization, and leaching while improving efficiency by a significant level. We are also stretching the fertilizer as one application done in this manner means we can sit out two or three future applications. Fortunately for Haley’s group, although we didn’t plan for the ban, we had planned for something else. It also gave us sufficient fertilizer and for food crops raised by workers, so they could infuse some so that they are not going to go without food.

Dananjaya – When you talk about ensuring food for workers, that’s a stark contrast to the situation for someone living in an urban area, isn’t it? People there don’t have the opportunity to stock food, and are relying on retail supply. There is no guarantee for them, as they might find themselves standing in a queue for days, and not be guaranteed any food at the end of it.

Roshan – The plantations you know, care for not only the direct workers, but all dependent family members. So if someone has got COVID, we say, don’t worry, we have given the family food over the year in some cases, we can recover it. So by that action, people have confidence in the management that we have looked after them in a very, very critical time. And when they were sick, we made sure that the government medical authorities or personal care management were involved. We offer a holistic total system of care for our people.

In towns, as you said, we all have to stand in queues, and those who do are not sure there’s stocks, but in our case, we bagged provisions and dry rations and brought it to their home so that they don’t have to come and interact or mix with people and spread COVID. So that way, I think we got a huge boost in terms of human resources. When we gave very tough guidelines and instructions, they followed the advice like keeping a distance while working whereas traditionally they were together in a row. We said you have to separate immediately and without any protest they showed wholehearted obedience and support for us.

Dananjaya Silva – Fuel shortages have crippled and decimated many sectors of the country what provisions and adaptations Hayleys have made to ensure the smooth running of operations.

Roshan – After the crisis came on, definitely we have taken radical measures to reduce the running of unnecessary trips and vehicles. We have mapped out all the roads in each division and compared distances and identified the shortest routes to make transport more efficient.

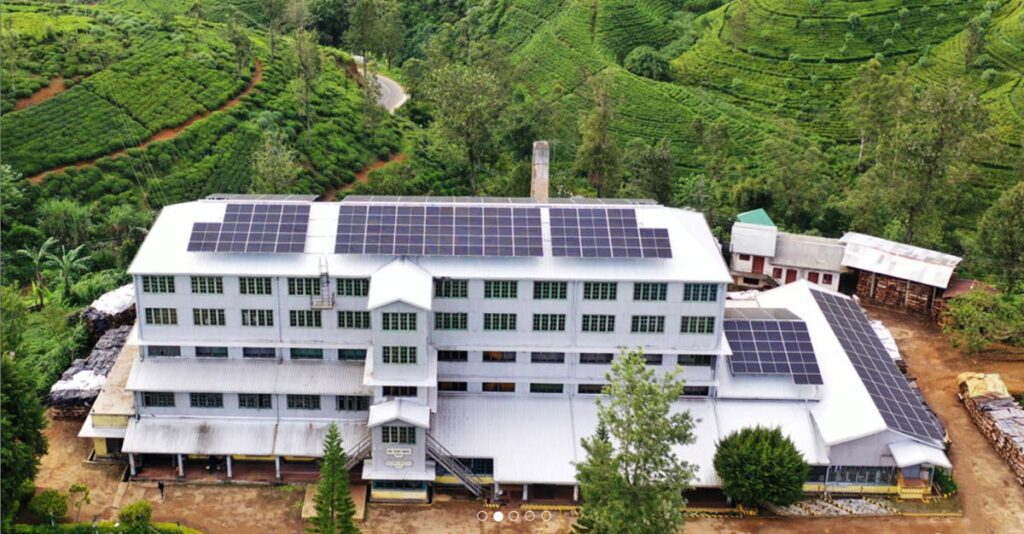

We also introduced some innovations like ziplines. These were built before the crisis, but came in handy. We can save about 90 kilometers a day on trips to the factory because the tea otherwise has to be driven along a circuitous route. It’s eco-friendly and does not use fossil fuel. We have instituted several eco-friendly practices. Now our managers and assistant managers are provided with good Push bicycles, and they have resorted to more walking,

“ We are maintaining the tea industry as it was before in spite of a lot of challenges, a lot of stress, a lot of issues.”

– Roshan Rajadurai

Dananjaya – One area that you touched on was moving tea from estates down to Colombo, there has been some disruption. How are you working through that situation because because the logistics are provided from from outside of the estate.

Roshan – Normally, we manufactured and made arrangements to send our produce to Colombo, and to ship it out. What we do is provide measured fuel to take the tea down to Colombo and even for firewood suppliers because we need firewood to run our dryers. So we assist them in some form. Because of the fuel shortage we are trying to harvest wood that is already grown on the estate for this purpose and adding branches cut to reduce some excessive shade.

All those initiatives and energy efficient measures add up. We are relying more on hydropower and we are trying to put almost 60 to 70% of our roofs in solar. So all those things can happen after the crisis. These are interventions that happened before COVID and the financial crisis, which have a beneficial use for us right at this moment.

Dananjaya Silva is the managing director of London-based PMD Tea and a third-generation tea man whose family business, P.M. David Silva & Sons, dates to 1945 during the Plantation Raj in Ceylon’s Maskeliya Valley.

Related

- Sri Lanka Responds to Tea Market Turmoil

- Protecting Sri Lanka’s 150-Year-Old Brand

- Q|A Niraj de Mel, Chairman Sri Lanka Tea Board

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.