Boba Guys make their drinks with real fruit, real milk, real foamed cheese, and real tea, brewed from loose-leaf oolong and other quality varietals, and served with tapioca balls made in their own factory. The bustling chain, now with 20 locations, was co-founded by Andrew Chau and Bin Chen. Chau, a featured speaker at World Tea Expo this week, explains how relentless attention to quality elevated a simple mix of milk tea and tapioca to a $3 billion global segment that is enticing a generation of non-tea drinkers to give tea a try.

- Caption: Andrew Chau, co-founder and CEO, Boba Guys.

‘We Really Push the Envelope for Quality’

By Dan Bolton

A business graduate with a master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley, Andrew Chau worked as a marketing planner and manager at Target and Walmart before co-founding Vergence Media, a digital imaging startup. He later managed e-commerce for Timbuk2, a consumer electronics venture, and worked as a global brand manager for LeapFrog, in Emeryville, Calif. In 2011 he and Bin Chen launched Boba Guys opening their first shop in the Mission District. In 2015 they launched Tea People. The company has since expanded with six locations in Los Angeles and one in New York City.

Dan Bolton: Why is bubble tea a gateway for exploring tea in-depth?

Andrew Chau: I hope I don’t insult anybody by suggesting that you need boba in order to experience tea. There’s a millennia of history with tea. I’m not saying that we’re rewriting all of that history. Tea is something that’s been drunk for thousands of years.

In certain countries, tea is normal, in certain places coffee is normal, in certain places mate is normal. Tea is basically a cultural product. When I say it’s a gateway drink, what I mean is that is how a lot of people get into tea. It brings you into the deep parts of tea; we’re talking about knowing what an oolong is, knowing where tea comes from in the world.

Knowing tea at that depth opens the gate.

There’s a drink that I really love in Taiwan, where my parents are from. It’s made with a high mountain oolong, a buttery tea that you put crema on top. The crema is like ultra milk, some people call it cheese. Sometimes you get a milk mustache drinking it along with the tea. It’s almost like a milk tea, and yes you are having tea with milk, maybe there’s some sugar in it. But what you are really tasting is the body of the drink, which in this case is an outstanding oolong, an Iron Goddess [of Mercy] tea with a milk cap or foam. Ten years ago you would have probably just ordered a Frappuccino.

And that’s how so many people get in. The idea is to get you interested in the tea. Sure it is called a “Frozen Summit Oolong” but drinking it you are starting to understand the profile of that fine tea flavor.

That’s what we do.

We really push the envelope. We source our own tea and sell it to different cafes across the world. Our tea brand pushes innovation, meaning that we do nitro tea because with nitro you have more body and can taste nuances that you wouldn’t get in a hot water steep.

What we do is get people involved.

A gateway is basically like a beachhead, right? It’s where people enter. So you enter the shop and order a simple milk oolong, a Tie Guan Yin, a familiar English breakfast tea, or a Ceylon tea. We capture the best qualifies of these teas in a bubble format.

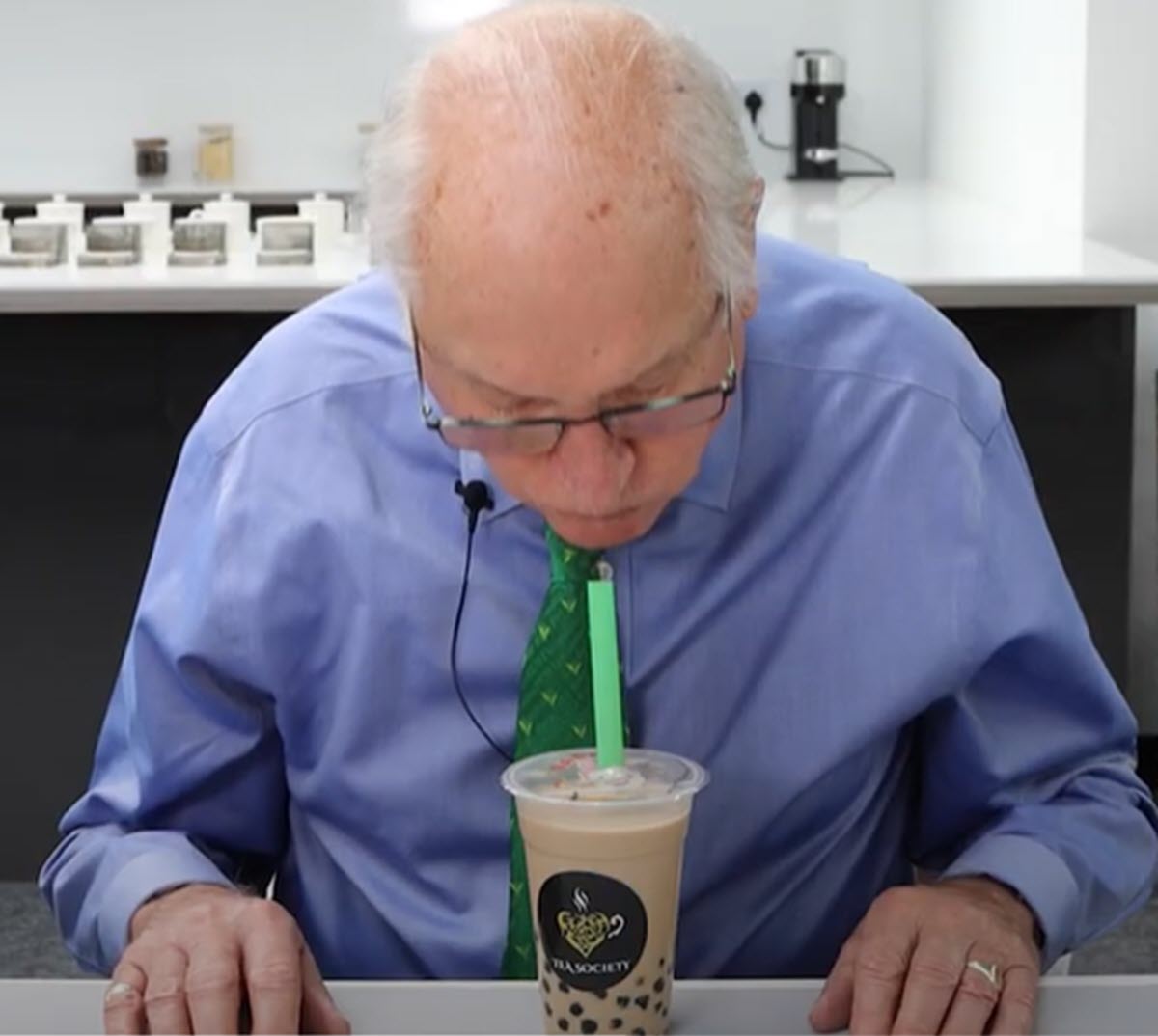

Dan: Your Boba gateway doesn’t have a sign on it announcing, “no one over 35 allowed.” Boba Guys shops are filled with people of all ages eating and slurping and conversing. They are animated and interact as they poke and play with their broad-diameter straws. Boba is experiential — a drinking occasion that mingles quality tea and a memorable experience. Will you talk about those aspects?

Andrew: People sometimes say boba is a fad. I’m like, well, how is it a fad if two billion people drink milk tea, or have tapioca every day? When boba first came out, it was a kind of dessert. Tapioca and cassava, the plant that it is made from, are native to Brazil. The Portuguese and Spaniards brought it to Southeast Asia. Similar to flan, you have cassava pudding, and cassava cake across Southeast Asia, in Malaysia, the Philippines, and other Spanish and Portuguese colonies. The pudding got mixed into a milk tea culture. In Europe, there’s a milk tea culture in the Middle East, and even in Mongolia and Russia.

So I think that what happened is that it caught on again, in modern times as a kid’s drink because teenagers drink it loaded with a lot of sugar. I was one of those kids, but as I got older my metabolism changed, so I have to watch that sugar.

When we created Boba Guys we purposely made it accessible. The format and taste profile are like what people want in a Frappuccino. We lowered the sugar content and used raw sugar. We make our own sugars. We don’t have any high fructose corn syrup in our stores. That is one way we made it accessible.

Consider matcha. Everybody loves matcha in a latte or shake, but many don’t appreciate matcha’s tea culture. We have tea classes at Boba Guys. I teach people ‘this is a Dragonwell, a Longing green tea,’ or ‘this is a sencha green tea.’ When you grind it up to make it into a fine powder that is essentially matcha. At Boba Guys we layer it into the drink. The technique is known as a pousse-café. You see the layer, it is visually separate versus one giant green mixed latter.

I explain that you’re drinking the entire tea leaf, whereas if you had a Dragonwell Longjing it would just be steeped. So you begin to understand how your body is internalizing all these anti-oxidants, like the catechins and ECGC. When you explain that to people you’re able to story tell. People haven’t been articulating the story of boba.

How do we make it accessible to Americans?

We explain that it is something to enjoy casually. If you want a slight tea buzz and you’re young and just are not a alcohol drinker. Go grab a boba.

That’s what we are seeing now. It’s become a hangout for people. You would never a decade ago hear a regular everyday American want to talk about oolongs. You would hear them talk about green tea and black tea. I think we have come a long way and we want to be much more inclusive.

“When I say it’s a gateway drink, what I mean is that it’s how a lot of people get into tea. It brings you deeper into tea, knowing what an oolong is and what is Pu’er, knowing where tea comes from in the world.”

– Andrew Chau

Bridging Cultures

The Boba Guys sell tea online and supply many cafes and shops. “We started Tea People because we wanted to share our favorite teas with our friends the only way we knew how, by keeping it simple,” said Chau. “We visit the farms ourselves and source our own teas. Our mission is to make quality tea approachable, so we try to make it intimate, straight from the source,” he said.

Related

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.