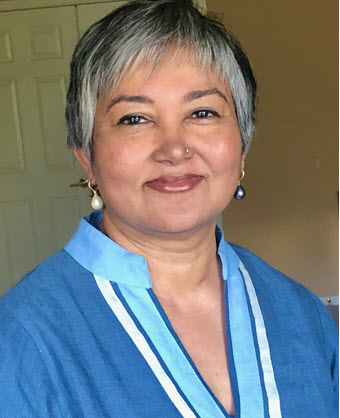

In recognition of International Women’s Day, Tea Biz spoke with Sabita Banerji and Krishanti Dharmaraj from THIRST, The International Roundtable for Sustainable Tea. Sabita was born and raised in tea gardens in Assam and Munnar. She is an economic justice advisor and the founder and CEO of THIRST. Krishanti Dharmaraj is a THIRST trustee and Executive Director of the Center for Women’s Global Leadership in New York and co-founder of WILD for Human Rights (Women’s Institute for Leadership Development).

Where do we stand with respect to workers rights, and women’s rights, in particular, in tea in countries like India?

Sabita Banerji: There’s a lot of talk about labor rights on tea plantations all over the world, but very much so in India as well. The majority of workers particularly at the lowest paid level, the tea pluckers, are women. The industry talks about women having delicate fingers and being able to pluck the two leaves in the bud. But when I’ve spoken to women workers, in the Dooars, for example, and asked them, why do you think there are more women employed at this level, they said, because we are easier to boss. So, you know, they are aware of their situation. I think the vast numbers of women working in tea plantations are kind of stuck at the level of tea pluckers. They don’t have the kind of education or the empowerment to be able to stand up for their rights as they should be. And so, it’s important to empower them because it’s the right thing to do. And it’s important because it’s such a major element of the tea industry.

Krishanti Dharmaraj: I want to say it is the right thing to do as well as it’s a smart thing to do. It’s important to recognise that there’s a structural nature to discrimination against women that is not limited to the tea plantation. We see that at every level, but when you take gender and intersect that with class, with caste, and with ethnicity, then at that point, the discrimination doubles.

So when you look at the women who are in tea plantation, and I can speak for Sri Lanka, this was the Tamil community that went, that the British took from India to Sri Lanka. They are at the lowest level. It was very recently that they were able to vote in Sri Lanka. So in that context, that systemic discrimination seeps through. And so when you see, even in spite of that systemic nature of discrimination, that women are rising up, that is extraordinary.

And I think the tea plantations, the businesses as well as government, must pay attention to that uprising.

Sabita: And that is the case on virtually every tea growing area all over the world, but particularly in India where the workers tend to come from another part of that country, a poorer part, a more vulnerable part. So, very often as well as being vulnerable as women, they’re also vulnerable as migrants, as lower caste, as tribal people as Krishanti said. There is a particular vulnerability there in the tea estates.

But where have you seen the change, where women have risen to protest this?

Sabita: I saw this first hand, in Munnar in 2015, and this is what inspired me to set up THIRST in the first place, The International Round Table For Sustainable Tea.

I had gone to visit my birth place, Munnar, and it just happened that that same day, the uprising of women workers, “Pembilai Orumai”(unity of women) had just begun. It was really an unprecedented event, that these thousands of women went on strike. And there were not only striking against management but also against the trade unions. They said that the trade unions are male dominated and that they’re not representing the women workers fairly or effectively. And so for, for many, many days, they, they stayed on strike. They did hunger strikes. They were not allowed to negotiate with the employers and the government as part of the tripartite pay negotiations because they weren’t a formal trade union.

But the chief minister of Kerala agreed to talk to them and agreed with some of their demands. And subsequently that group of women has formed a trade union. So, you know, it probably is one of the few, genuinely representative of women workers, trade unions that there is in the tea industry.

Another example is a cooperative called the Sanjukta Vikas co-operative in Darjeeling which runs a tea garden called Mineral Springs. This was originally a British era tea estate which was closed down when the British left and the workers were left pretty much destitute, which is still happening today.

All over India, estates are closing and the workers have no other source of income. But this group managed with the support of a local NGO called DLR Prerna and tea promoters to actually form a cooperative, which involves several villages around the area. There has to be a balance of men and women and women have an equal say in how that co-operative is run. And they’re growing not only tea but they’ve now diversified into other crops, and they’re doing dairy … the tea itself is really good quality. It’s organic, it’s fair trade and it’s doing well.

What’s enabling this show of strength? And what kind of support do these women need?

Sabita: In the case of the women from Munnar, I asked them that question because everybody around me was saying, we’ve never seen a strike like this before. And I think the local, townspeople were quite impressed with the women being strong and standing up for themselves.

I was asking them, why do you think this has happened now? How are they now aware of their rights? They were saying that they were underpaid, their bonus was being reduced from what they were expecting it to be and they responded with just one word: WhatsApp.

With the younger generation being on WhatsApp and I think that the uprising itself was pretty much coordinated using social media. That’s one thing, information and communication but also the strength and determination of these women themselves. What they need, in addition to their own strength and determination and information, is support from other trade unions, from local people. During that strike, they were fed by the local shopkeepers, and hotel keepers came and supported them.

They’re now a very small trade union. They only have about 240 members, at least when I last spoke to them, that was the case. And then not really being heard by management. So I think they need more support perhaps from other trade unions, from the company itself. The tea company should be valuing this amazing resource that they have in their midst, of these women who are able to really genuinely represent their coworkers, and to tell them what they really want and need, and to respect those wishes so that they have a contented and thriving workforce.

Krishanti: To add to that, I think it’s important to also recognise where they land, because this is not a group of women where after they finish work, they could go home and relax right there. They’re also taking care of their families, their in-laws, they are part of a community, and children. In most cases, they also face domestic abuse. Intimate partner violence is pretty high.

When you see a woman really receiving her pay check, her face looks very different on that day than any other day. So part of it, and most of the time at least for Sri Lanka, there was a time where the husband got the money because he was able to sign for the pay check, even to put the thumbprint.

There’s been a shift. For the first time, to be able to feel like she is the caretaker of her family and because of her hands. She is the caretaker because it is for her hands that the entire family gets not only paid but has the ability to just stay in that steady state.

So what we need to recognise is that if she is taking up to actually striking and pausing her work, that is not an easy decision for her. She’s got to really realise that there’s no other way, but to strike. There’s no other way out. So it is not a decision that the women in the tea estates would take lightly. They would take that decision only because there is nowhere else to go. But at that moment, when they choose to, when they have made that decision, then there’s nothing else that will stop that. Because there’s nothing else to lose.

When you saw the uprising where the women were striking, where were their husbands and children and other family? Were they with them?

Sabita: The women actually refused to allow their husbands to join them.

The women were all sitting on the ground, outside the head office of the company and the men were in a side street. They were kind of messing around and they had thrown lots of tea leaves on the road and they were picking up these tea leaves and throwing them at passing cars and laughing. It was a kind of festival atmosphere for them. They were being like naughty school boys.

And meanwhile, just around the corner, the sea of very serious women were sitting there. They had brought not only the tea industry to a stand still that day or that week, but also the tourism industry, because they were sitting on the main road through Munnar.

They were not to be messed with, those women and they were very consciously keeping the men out of it because they were saying, we are the ones that do the work and so we are going to speak up for ourselves.

What would you say to this display of strength? What has it taken them to arrive here?

Krishanti: Centuries of oppression.

To me, there are three things:

It’s the timing and the networking. WhatsApp is one extraordinary way that people are able to organise. The first thing is that it’s not that women don’t know their rights. Innately, we know, even as children, when someone does something to us that is not right. These women know. They do not believe sometimes that they have the ability to speak up and protect themselves because the consequences would be much harsher if they speak up. So I think the rights are already in place when they have a space to articulate them.

And then moment to express them. They will take that up. And I think now more than ever, it’s almost in the air when you look at the informal sector. And in this case, I think the tea plantation workers are considered formal because they are able to unionise. There is a movement within a movement to see that those most marginalised are rising. And I think that’s in the air. And we cannot deny that it’s sweeping across the globe. With the extraordinary amount of oppression that women are facing at this level, there is a moment that is right. And I think they’re picking up on that.

Assam faces the flak in the conversation around workers’ rights. Why? What can you tell us about that?

Sabita: I’ve always wondered why there is this intense focus on Assam. I mean, this situation is very difficult there for, for workers, but it is probably worse in the Dooars, in West Bengal, in Darjeeling as well. Despite Darjeeling tea being a high value export commodity the same issues apply in any tea growing area. In terms of what’s happening in Assam, currently, there has recently been a small pay increase. Last September, many hundreds of thousands of tea workers there had gone on strike and that was a trade union organised strike demanding an increase in wages to 351 rupees a day. Which funnily enough is what the government had recommended back in 2018 and yet has never been implemented. So they’re only asking for what the government has recommended, in a system where they’re supposed to be tripartite wage negotiation.

So, you know, you can see there’s something not quite right with this system where workers are still being paid so much below the living wage. To come back to the question that you asked about the men, and it also links to something Krishanti said about domestic violence — one of the issues is with the fact that most of the tea pluckers are women — and the industry relies very heavily on that labor — one of the side effects of this is that the men on the tea estates tend to be underemployed or unemployed. And this leads to a lot of problems like alcohol abuse, drug abuse and domestic violence. Often men will migrate away from the estates to try to earn money elsewhere. Sometimes they don’t come back or don’t send money back. This causes a lot of societal problems, the fact that there’s so much pressure on the women, not only to do all the unpaid domestic care work, but also to do all the labor as well.

Often organisations come along and suggest solutions like alternative income generating projects, like having a cow or having a kitchen garden or something … that too is something the woman has to do on top of everything else.

One of the women I met in the Dooars told me that yes, we had a cow at some point, but I couldn’t look after the cow AND pluck the tea AND look after the house. So we had to sell the cow. Like we were discussing before, there needs to be a whole change of mindset about how this industry is structured and how it operates.

Krishanti: One of the things we haven’t talked about is the level of harassment and violence these women face in the job as well. So they face discrimination, harassment, and violence at home, right in the community as well as at work. Then there’s structural discrimination that discriminates the entire community.

How can we persuade producers and governments to look at it from a woman’s point of view? What is it that we need to show them?

Last year, the international labor organization passed a convention called ILO 190 to eliminate harassment in the world of work. So there are things that I think that’s important to recognise. One is that the convention talks about harassment and violence against men and women. And harassment is not limited to sexual harassment. It is a broader definition, That is extraordinary because that allows us to really address the systemic nature of discrimination. And it talks about the world of work. The employer is responsible for ensuring and enabling an environment for the workers to thrive. Because it’s the ILO, it speaks to government, it speaks to employers and unions. This particular treaty, if ratified and implemented, it might support the shift in this structural systems. Because it is not one system.

What would you say these women want?

Sabita: The women were demanding better pay, they were demanding all the things that are promised to them under the Plantation Labor Act, which was, you know, decent housing, healthcare, education. A lot of outsiders look into the situation and say, actually, this situation is not really sustainable. A company can’t provide all those things that a government would normally provide AND pay decent wages, especially as they’re not being paid necessarily a very fair price for the tea.

But when you talk to workers themselves, because they’ve been in that situation for many, many generations, it’s sometimes hard for them to see what life might be like, without all of those supports. So often they say, no, we do want to keep the rations and the benefits that are provided rather than … it’s just, it’s almost like, their prison is also their safety net.

In Sri Lanka, there have been some attempts to set up community development forums, attempts to actually give the housing and the land to the workers. So they’re not lines which are just connected to be owned by the tea company, but they are actually owned by the workers and then that developed some pride in their own.

Krishanti: I think I wanted to just step back to say that in the context of existing systems, yes, they want the basic rights. If you pause and if you allow them to speak freely, and if you allow, if you give them the space to imagine, that imagination runs wild and that is completely out of the existing structure.

Within the existing structure, like when you talk about Sri Lanka, yes, there have been attempts as well as successful ways in which women have inherited land, in partnership or by themselves. But most of the time it’s written to the man because of an inability to do that. Sri Lanka has one of the highest literacy rates — it’s close to 90+ percent, but in the tea estate, they barely make it, they’re unable to even sign their name. Now we have provided them the ability to sign their name when they take their pay check. But that is all they can do.

Sabita: In Indian states like Kerala, there are very high literacy rates and other kind of social standards, but not on the tea plantation. So, the disparity is extraordinary.

Krishanti: If you take it within the context, yes, they want to make sure that the housing is there.

They want running water. They want to have toilets that have doors. They need to be able to take showers. So, when you’re looking at the basics, they are looking at economic, social, and cultural rights to be in place that India and most of these countries have already signed on to that human rights treaty. And it is only provided for some not others. Education. They want everything that any regular citizen would want. Access to education, housing, healthcare, decent work sanitation, right. To express themselves, you know, in their job.

Sabita: About education, everywhere I went, every tea worker I spoke to wanted to get a decent education for their children so that they wouldn’t have to work in tea plantations anymore.

Krishanti: When you ask, is there anything else you want, the first thing they say is I want to be treated well as a human being, with respect. They know they can’t get in the system. So, they will compromise that right to dignity to have the basics for their family.

So, it is about the treatment. It is about the inherent right to dignity that is violated on a daily basis because of the way in which structurally they are discriminated against as a community, as disposable humans, who they cannot dispose because they provide a specific service for a massive industry.

Sabita: Krishanti talking of them being disposable. … in fact, that’s exactly what is currently happening in Kenya where there has been increasing amounts of mechanisation. For example, Finlay’s has been laying off thousands of workers and bringing in machines instead, and it’s mostly women who are now losing their jobs as a result.

In Malawi recently, there has been an interesting development in which Camellia, a tea company that owns many local tea companies there, has agreed to a settlement for women who made claims of sexual abuse, rape, and sexual violence. Camellia, thanks to the work of Leigh Day lawyers have not only agreed to make a settlement, but they’ve also agreed to put in place other initiatives to actually empower women and protect them going forward.

When you ask, what do women need, I think some of these. And what do they want? Some of these things that the settlement includes, like gender equality, scholarships, female leadership training programs, which hopefully will also be accompanied by the willingness to engage women at more senior levels.

But these are all things that we’ll add to. Women, not only attaining their rights, but as Krishanti said, feeling that they are being treated with respect and with the dignity that any human being deserves.

Krishanti: When a woman loses her job, it’s not just her losing a job that is that entire family’s livelihood is at stake. We need to understand it is not only that the woman loses. And that’s an entire company, community’s livelihood and the quality of life that is at stake. And that in itself is an economic threat to any government, to have that many unemployed or underemployed. So I think when you ask, what do the women want, if we pay attention to what women want it is what a country wants. So you can take it from a holistic standpoint and say, if you really believe in democracy and human rights for all the people as leaders, then you need to listen to those who are in the margins. Because without them, there wouldn’t be democracy. We can talk, it will be rhetoric. And for a business, it is that a happy worker, is a more productive worker. As individuals, if we’re in a better mood, we can get a lot more done. But if we are beaten up every day, that is a very different conversation to be had.

Paying attention to what they want and the way they want it, I think is the trick and the importance of it, not what a company, the industry or government believes they should be given.

Sabita: That idea of a happy contented worker being more productive was actually quantified. Care international produced a paper on the business benefits of empowering women tea workers in Sri Lanka, which actually showed that the productivity increased. But of course that shouldn’t be the reason why companies should do it, but this should be reassuring for them.

Also, there are so many long-term benefits. The younger generation don’t want to buy tea that’s been produced using slave labor and sexual harassment of women. They increasingly want things to be ethically produced, environmentally friendly. And if it’s not, they will know about it because of social media. And so, I can visualise a future in which tea is not grown in plantations, but it’s grown more like in Mineral Springs where it’s interspersed with other crops ,where there’s cooperatives or other business models as well, but ones in which the producers have a say in their own future and are fairly paid.

This tea plantation model, which was set up 150 years ago — it’s still that same model — is just not appropriate for this day and age. They’re huge monocultures with a captive workforce. It just cannot continue that way. It needs to be really shaken up and something beautiful and dignified and, healthy and thriving needs to come out of it instead.

Do you think mechanisation is one of those things that’s going to bring about this change?

Sabita: There are some limitations to where mechanisation is possible. Tea is mostly grown on slopes and it is quite difficult to mechanise tea plucking in hilly areas. Also, tea that is plucked using machines is not as good quality because it can’t actually differentiate the leaves as well as a human can. It’s possible that a lot of the lower value, high volume tea will end up being harvested through mechanisation as it’s happening in lots of other sectors like tomatoes and grapes and so on. But there will always be a space for high quality tea to be plucked by hand, like the Darjeeling first flush, which is very valuable. And hopefully, those who use that recognised skill will be fairly rewarded.

Is it about holding the producers more accountable?

Sabita: I think that the problem is that the tea industry has an almost 200 year history. There are all these defence mechanisms. So the minute any criticism is made of the tea industry, they immediately go into defence mode and deny that it’s happening. They will say, you’re just victimising us or it’s politically motivated or, or that was just an isolated incident. It’s not true. Or the workers are lying to you. That’s not the case. So unfortunately, they know what the problems are. They know what civil society thinks the problems are and what the workers say the problems are. I think what they need now is, is to understand that the, that the consumers will no longer stand for it.

We now need to look to the future and try to work out a way of growing and selling tea that actually aligns with the sustainable development goals, be that through, at an environmental level or for decent work or ending poverty or ending inequality, all of those things.

Krishanti: I think we have to really recognise that what we are doing is perpetuating aspects of colonialism in these estates. That is like the first realisation and to really sustainably transition, you can’t just break it down overnight and destroy the well being and the ability for communities and individuals to live. I think this is where the collective power of the government, the industry and the workers needs to come together. Even the best estates, even when women and the workers are treated well, the model itself is not sustainable, right. It doesn’t allow humans to thrive. And I think that this sense of coming together to come up with solutions is important.

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Subscribe to the Tea Biz newsletter and view archive

Subscribe and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

One response to “Women’s rights in tea with Sabita Banerji and Krishanti Dharmaraj”

[…] “Tea workers are trapped in a 19th century system that creates poverty and suffering,” says Banerji. “You can’t just break it down overnight and destroy the well being and the ability for communities and individuals to live,” adds Dharmaraj. “I think this is where the collective power of the government, the industry and the workers needs to come together,” she said.Read more […]