Have you ever noticed a colorful sheen on the surface of your tea? It appears brittle, breaking like ice floes in the Arctic as the tea cools. Researchers once thought it formed from waxy substances in leaves released during steeping. That is not the case. The delicate film is an interfacial interaction of air, tea polyphenols, and calcium carbonate ions in water. It does not form on white, yellow, green, or lightly processed oolong teas; it is only black tea. Soft water in many parts of the world prevents the film from forming. Is tea film a fleeting glimmer of color to enjoy or an unsightly scum that dissipates with a squeeze of lemon? Or does it? Caroline Giacomin, a student at ETH Zürich in Switzerland, joins us to explain the physics of tea film from a study she and colleague Peter Fischer recently published in the Physics of Fluids.

Listen to the interview

What Causes the Film that Floats on Black Tea?

Caroline Giacomin is a Ph.D. Student at ETH Zürich in the Department of Health Science and Technology. Her early research focused on optimizing a fluidized bed reactor within a CO2 direct air capture system. She previously worked on the rheology of sugars and most recently published her studies on the interfacial rheology of tea.

Dan Bolton: Thank you so very much for joining us on the program. The topic is fascinating, and I see that it’s already getting some press attention. Let’s talk first about what made you curious about what some consider tea scum?

Caroline Giacomin: I was working somewhere where the water was particularly hard, and one of my colleagues said, during our afternoon teatime, that he doesn’t drink tea anymore because he doesn’t like the stuff that is floating on top of it. He’s from Taiwan and had never seen tea scum before or tea film.

I had never really thought much about it. Sometimes it was there. Sometimes it hadn’t been there.

I went home and looked up how to get rid of the film for him. Turns out you can add lemon juice. Everyone on the message boards will say that it’s not a particularly scientific answer but obviously a traditional one.

I didn’t really worry too much about that at the time. It wasn’t in my realm of research, but when I came here to start my Ph.D., our professor shared a list of ideas he thought might be interesting to investigate. We studied interfaces in this group, and on his list was tea interfaces. And I said, “Hey, I think that’s an interesting topic, and I’ve looked into it before.”

So that’s how.

Dan: What a lovely story. And I applaud you for thinking broadly. In science, it isn’t just narrow routes; it’s a wonderful opportunity to appreciate broader everyday applications in the world around us. So, how did you determine what caused the film?

Caroline: A researcher from England in the 90s wrote a 14-part tea series, six or seven of which were about the tea film. And so I followed in his footsteps. He was studying the components of the tea film, and since we work with interfacial, I studied the strength of the film that forms on tea and with tea with additives like lemon juice, sugar, milk, etc. He did the composition now we’re studying physics instead of chemistry of it.

I based the choice of add-ins on his research.

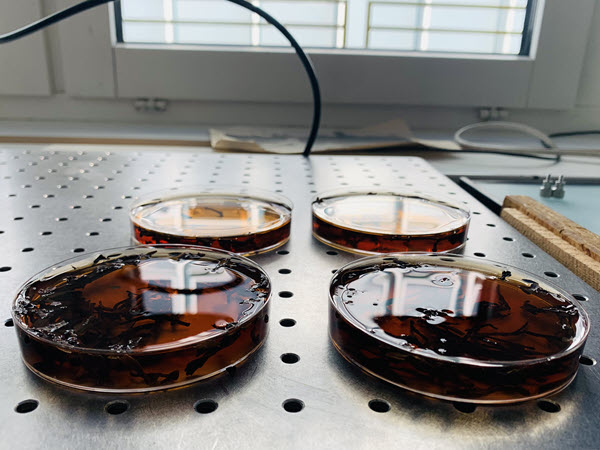

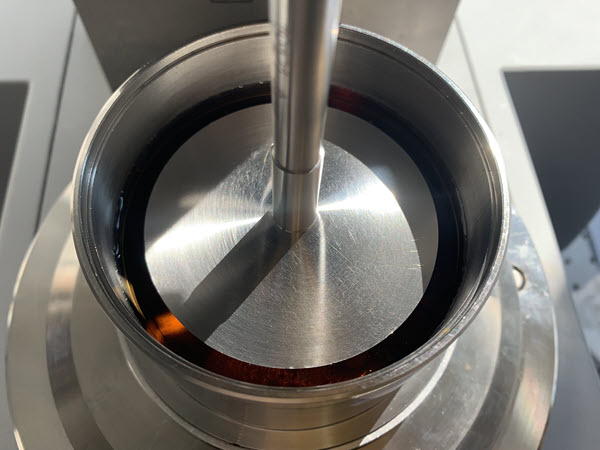

Rheology is the study of weird fluids. Think about oobleck, the cornstarch and water mixture kids like to play with, or slime [Popularized on Nickelodeon]. Or you about measuring how shampoo or molten plastic flows. That’s rheology, and bicone interfacial rheometry means we’re dealing with the rheology at the surface between two phases.

In our case, we’re dealing with liquid tea and air phases. Interfacial rheology uses a metal device with a disk that contacts the surface. Then, we carefully control the movement of that disk. A motor controls the movement, and a sensor detects exactly how much force the motor applies. That can tell us how brittle or how elastic the film is. When you know exactly how much force is needed to break the film, you can determine the depth of the film, the thickness of the film, and its elasticity.

Dan: The thickness, then, varies with the amount of carbonate in the water, but it isn’t the critical factor. It’s the viscosity, the resistance to movement of the metal plate. How do you describe the film regarding its physical characteristics instead of its chemical components?

Caroline: In our field, we use the phrase moduli. The elastic modulus describes the film’s elasticity, flexibility, and stretchiness. If you move the film a tiny bit, will it reform itself back into its original position? The loss modulus gives you the brittleness of the film.

Dan: You’ve described the physics. The chemistry was previously described as tea polyphenols bonding with calcium carbonate ions at the surface to create a colorful sheen. Are there practical industrial applications for your research?

Caroline: Conditions forming the strongest film, chemically hardened water, may be industrially useful for preferable shelf stability in packaged tea beverages and for emulsion stabilization of milk tea products. Conditions forming weakened films by adding citric acid may be useful for dried tea mixes. You are not likely to see the film in bottled tea because the bottles of iced tea you find at the store generally have citric acid or other preserving acids to extend the shelf life. But, those same acidic components cause many of the purported health benefits of tea to be dramatically reduced within the first 24 hours after bottling.

If you had a pure tea product on the shelf in a bottle with no preservatives, no sugar, no citric acid, you would see little bits of the film sticking around at the top of the bottle, which most people would find extremely unpleasant — like you’ve got mold growing in your bottled beverage, and that wouldn’t be good.

Also, it may be helpful to market teas with citrus in certain areas with very hard water. If you compare cups made with the same water, Earl Grey would have less of a film than pure black tea because it has bergamot, which is a citrus component.

Dan: When making tea, should I be anti-scum? Should I dissolve the scum to get rid of it? Or should I appreciate it for what it is and not worry? Is tea scum an indication that I need to do something with my water? Based on your research, what practical guidelines do you suggest for making or enjoying better tea?

Caroline: It depends on what you think is best for tea because the film, especially when you don’t add milk, the film is quite beautiful. (I’m a scientist describing tea scum as beautiful). But when you add milk to tea, it is often not visually pleasing. It can look gross. The film that appears after adding milk is different from the tea film. It’s made of very different components. This is why, in my research, we couldn’t measure the resistance of the milk film because there’s too much oil and fat in it to be measured by our device; it caused too much slipping, essentially. So those two films are different.

Now that I know what it is, I like to see it. If you like the appearance, you don’t have to do anything to your daily practice.

If you don’t like the film, make black tea with lemon, and you won’t see it. There will still be a physically strengthened film there, but you won’t be able to see it. If you are making tea to have milk, put the water through a filter. If you’re living in a place where the water isn’t particularly hard, that shouldn’t matter too much, and you won’t have much of a film anyway. That’s all that really matters at that point.

There’s nothing harmful about it. The film doesn’t affect the flavor. It’s more visual than it is olfactory. It won’t affect the aroma and the taste of the tea. It’s just a quirk of drinking tea.

— Dan Bolton

Resources

Share this post with your colleagues.

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

Episode 35

Powered by RedCircle

Episode 35 | Researchers once thought tea film was due to waxy substances in leaves released during steeping. That is not the case. The delicate film is an interfacial interaction of air, tea polyphenols, and calcium carbonate ions in water.

One response to “The Physics of Black Tea Film”

The study, undoubtedly thrown light on a new area in tea brew. Is there any relation between the tea cream and formation of film? What are the consequences of tea film on our health in general and digestion in particular?

Regards.