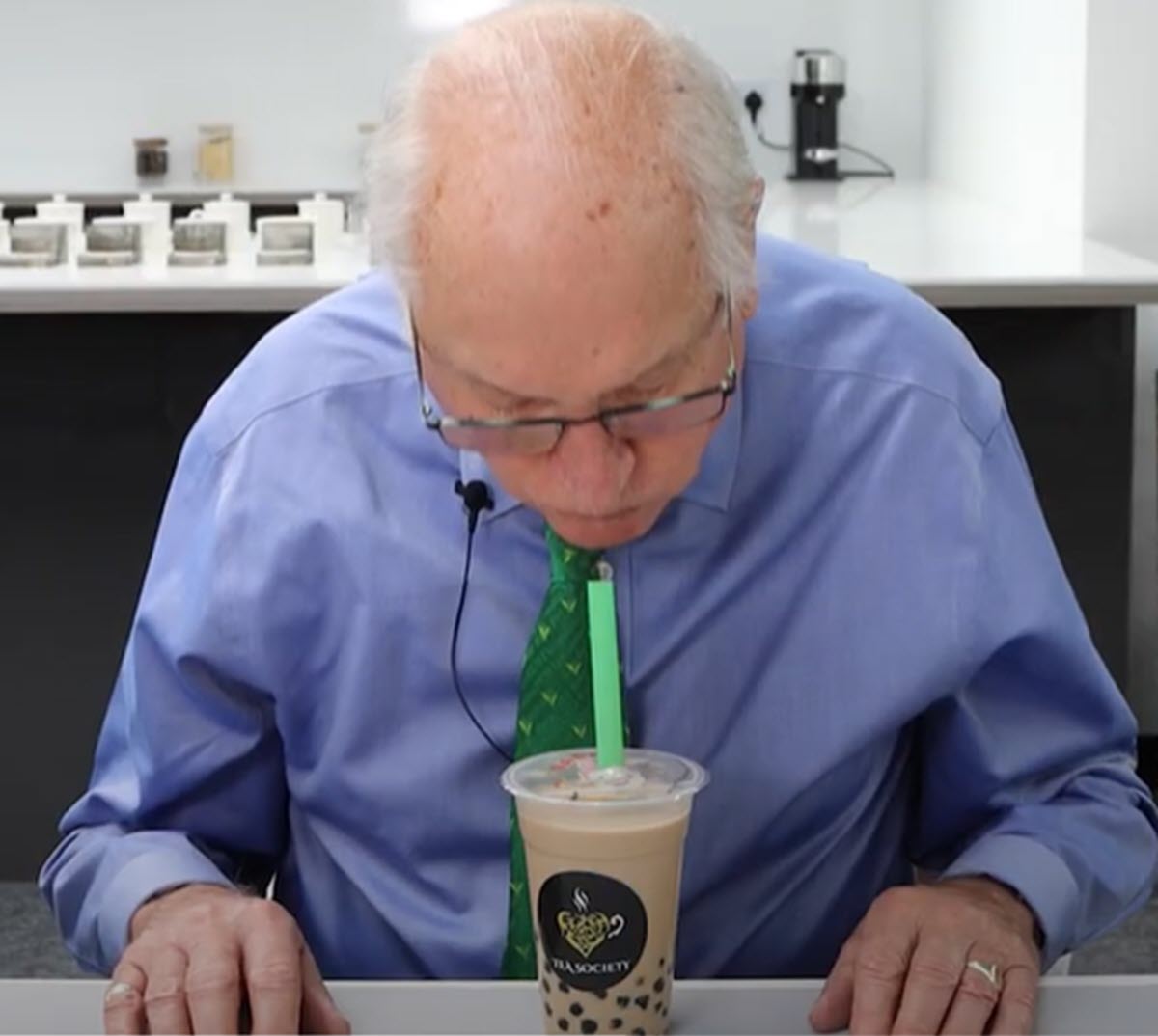

Mike Bunston, OBE (Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) is chairman of the London Tea History Association, honorary chairman of the International Tea Committee and serves as Sri Lanka’s Tea Ambassador. He began his career in tea at the Wilson Smithett & Co. brokerage in 1959. Bunston recently visited the Tea History Collection in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to videotape a tasting of modern teas, including milk tea, a Jasmine-Mango fruit tea, and his first taste of bubble tea. Charlie Shortt, co-founder of the Tea History Collection organized the tasting and narrates this exchange.

- Caption: Mike Bunston, OBE, concludes his first tastings of bubble tea, fruit tea and milk tea with a chuckle.

Hear the tasting soundtrack

See the video

Hear the interview

A Taste of Modern Tea

I’m Bernadine Tay, founder of Quinteassential teas and one of the founding directors of the European Speciality Tea Association. Join me as Mike Bunston shares his insights into modern innovations in tea after his very first tasting of bubble tea.

Bernadine Tay: When you were first asked to taste bubble tea, did you have any expectations of what this could be? Having tasted millions of cups of tea as a tea taster, what do you think of the texture of the chewy tapioca balls? Or the fruit chunks in this colorful, customizable, Frappuccino-style beverage?

Mike Bunston: I naively thought bubble tea meant it literally had bubbles in it. Because I had tasted a tea champagne, which was made purely out of tea, and I thought it must be something like that. But it was nothing like that at all. It’s totally different.

When I took my first suck, I first got liquid and then got the meal as it were, oh my goodness me. This is an extraordinary sensation. And then of course, they put the three in front of me — very different ones. And the irony was that they [the organizers] had made secret packs as to which I would like best and worst. The first two were sweet. One was just like a smoothie. The second one was more like a sweet orange type drink, a bit too sweet for my taste. But I enjoyed it nevertheless.

As the third one was set in front of me they said “now this one is very different”. It had something like sweet potatoes in it. I believe it was Taro, which made the drink purple. The color was slightly off putting, but I soon learnt it tastes good. It was an attractive drink. And this certainly appeals to the younger generation. I’ve got grandchildren ranging between 20 and 36 and I haven’t had the chance to ask them if they have tried bubble tea.

In regard to the bubbles, my initial view is we could have probably done without the tapioca balls. Then as I got chewing I thought, “this is quite interesting”.

I can see why this attracts people of this generation. A real get up and go by it. You can walk through the street and drink it, if you’re in a rush. A total contrast to the traditional ways of drinking tea, with a teapot and cup. It is fascinating, and clearly they’ve got a great thing here, especially with the colorful and customizable options. The Taiwanese have always been great innovators, for everything.

Bernadine: Innovation is about creating something new that solves a problem. Do you see that with bubble tea?

Mike: If you’re a young person working in London, or any major city in the world, you’ve got a short time to have lunch, you’re out and about and want to meet a friend. You pick up one of those and suck it and chew it as you go along. In a way it’s almost as good as a meal, isn’t it? So, I think it’s trendy and practical, but it gives you all the goodness that you want from tea and everything else with this little added thing with the tapioca bubbles. So I think it’s clever.

Bernadine: The mark of good innovation is its staying power. So do you think bubble tea is here to stay?

You’re right. It begins with an idea that gets improved upon over time. It might take a while for it to gain a foothold, but if it works then there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be there forever. I think, in the case of bubble tea, I could have said without knowing much about it that I expect it’s just another fad. Having heard much more and tasting it, I think it’s got staying power for sure.

In summary, I love tea. When I talk about tea, I talk about camellia sinensis. So, anything that has got tea in it, I’m happy with. What I’m not happy with are all the things that say they are tea on the supermarket shelf, like mint tea, or fruit tea with the fruit and no tea. That really upsets me. But if it’s got tea that’s just a great thing.

They’re using tea as a base to make bubble tea and bringing it up, as you say, to the 21st century.

I think what people can do nowadays, with modern technology and all the bright ideas people have, all things are possible.

“I love tea. When I talk about tea, I talk about camellia sinensis. So, anything that has got tea in it, I’m happy. ”

– Mike Bunston

The Tea History Collection commemorates the history of tea, and preserves important items associated with the industry. Viewings and reservations for meetings are by appointment at the privately owned museum and audio visual center in Banbury. To learn more, visit www.TeaHistory.co.uk

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.