A recent development in tea in India has been the rise of new brands, many that have their roots in tea regions. Almost all of them seek to bridge producers and consumers. Most rely on the narrative that accompanies a product from its place of origin. For consumers, it’s in part vicarious living and a window to another world. This is as good as it gets for those who want to know who made their tea and where it comes from.

Listen to the interview

Exceptionally Local Teas that Connect with Consumers

By Aravinda Anantharaman

Emphasizing the local characteristics of Assam (instead of crafting tea to the expectations of export markets) shows respect for the land, customs, and artisanal craft, according to Folklore Tea co-founders Subhasish Borah, an urban planner, and Bidisha Das, a business management grad.

Folklore Tea, based in Guwahati, actively works with farmers to become something more than a marketing platform for their teas, explains Borah, 30, and Das, 29. The couple run the Kohuwa Collective, a space that comes with a slow food café and tea room, with rooms for collaborative clothing and pottery workshops – concepts that seem to drive their work. They launched Folklore early in 2020 and, as a brand, are keen to carry the farmers’ stories.

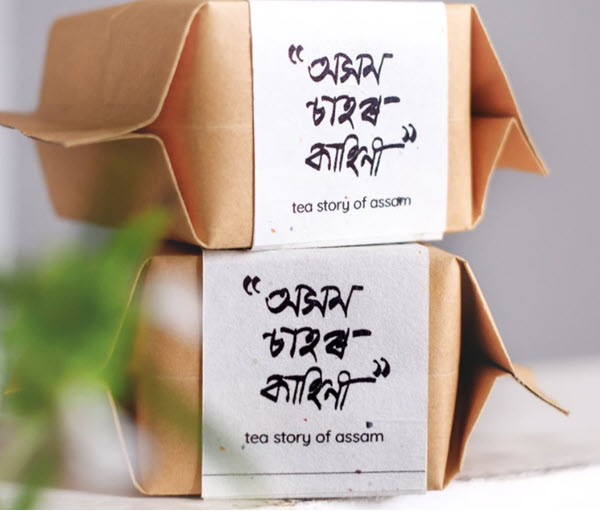

Folklore is anchored in the idea of storytelling and connecting to consumers intimately. Each tea acknowledges the farmer who grew it. Each tea is given a name, and a poem accompanies it.

Each eco-friendly packet is numbered with a handwritten note addressing the recipient. And while this helps connect with the drinker, it’s not Folklore’s unique sales proposition. That lies in the experiments and work they do with their farmers.

Folklore works with three small growers, Beeman Agarwalla, Birinsi Borah, and Tarun Gogoi, who collectively cultivate about three hectares (seven acres) of tea. They also run Prithivi, a farmer producer company that now includes 56 members with farms ranging from 0.2 to 3 hectares in size. All the growers are geographically located close to each other, making this a community enterprise. Beeman, Birinci, and Tarun have chosen organic farming and work with the other members to convert inorganic farms to organic. The process takes a long time, up to five years, during which farmers have to face a loss in yield and income. The association supports them by way of small scholarships for children and providing compost from a small vermicomposting unit.

“Behind it all, there are real people – small tea growers whose innovation improves the craft and whose land stewardship protects the environment and the quality of your tea. It is their passion that makes the tea taste better.” – Folklore Tea

In Assam, small tea growers sell their green leaves to bought leaf factories that manufacture and sell tea. Most of these factories make CTC tea, which is bought and blended for the domestic market. Farmers adopting organic cultivation find no advantages in price as CTC factories are not always organic. Here, the tea is mixed, and the source and style of cultivation are lost. With no advantages to producing organic tea, the farmer has no incentive to stay the course. And this is something that Folklore is trying to address.

Subhasish describes a proposed project for a mini-community factory that will be used to manufacture organic CTC with leaves sourced from their own farmer community. Currently, they have six small units where their tea is made. These units are not heavily equipped with machinery, and even the CTC is made using traditional wooden tools.

Related: A Local Movement is Brewing in Assam

“Right now, there are 56 growers who have joined us. So, collectively, whenever we will be able to set up the factory then we have a huge leaf bank. If we get this funding, which I’m not sure we will get, then of course we go for CTC as it will help not only these three people but all 56 families. That means almost 180 people will be benefited with this factory, it will be huge change in the village,” he said.

“Whatever we can do in terms of packaging, design, or marketing will help them,” he said.

Folklore’s association with Prithivi is a close and mutually beneficial one. Prithvi and its farmers brought knowledge of cultivars and tea making, along with market intelligence. Says Subhasish, “Most of the small tea growers with whom we are working started back in the early 1990s. They planted whatever tea bushes they could get from nearby tea gardens. The knowledge of cultivars was not very prominent at that time.”

The Folklore team decided to study tea and brought knowledge and the willingness to experiment in tea making. Their experiments are with clones, leaf-to-bud ratio, and processing methods such as pan-roasting and naturally scenting tea. Only a small volume of made tea, not more than 300-350 kilos, is sold under the Folklore brand, primarily black and oolong whole leaf tea and some CTC.

They are experimenting with rolling techniques to improve appearance, experimenting with blending to get the right flavor. And they have also taken on the immense challenge that oolong brings to tea making.

Artisanal tea making is still has a niche market within India. Folklore seems conscious of this, taking a B2C approach for India and a B2B platform that caters to a global market, with customers in the US, Canada, UK, and Australia. Since the scale is still small, the brand can sustain its relationship and customer base.

As Subhasish says, there are two main challenges and opportunities of Assam’s tea industry: people who live in the tea areas of the state don’t know enough about loose leaf teas. The irony of producing one of the finest teas and yet sending them to faraway markets is the story across India’s tea-growing regions.

“It’s very sad,” says Subhasish, “because people in their own region, especially in the villages and towns that are surrounded by tea gardens, the people don’t know much about loose leaf teas. It’s absurd that mainstream media is promoting the concept of green tea in Assam. Green teas have been grown here for years. It is supposed to be the other way around,” he says.

“Paying 500 rupees for a kilo of tea is not a thing here,” he says. The economic status is not very high. Assam’s annual per capita income is INRs 119,155 ($1,700 compared to the all-India average of $2,100 per capita).

“People collectively have less money so marketing loose leaf teas at a higher price is difficult. It takes a lot of effort to make loose leaf tea and if you’re selling it for let’s say INRs 300 to 400 rupees per kilo then it’s not giving me anything.

“Consider that you can get a kilo of CTC for INRs 90 to 100 rupees ($1.20). In this scenario everyone is going to buy CTC but it’s weird. In Assam the culture of water-based tea is also very high but that water-based tea is made using CTC, not loose leaf teas.

“Most of the growers face difficulties here, they don’t have the human resources or the financial resources to do marketing or packaging. Many people who start making teas go back to selling fresh leaves so that they don’t have to think about marketing again. And many people go back to inorganic because if they ultimately have to sell the leaves to bought leaf factories then then there is no point in maintaining organic because the factories are not certified to process organic tea,” he said.

Due to financial limitations, few of our growers can afford the expense of the organic certification process, but the growers are far beyond it. They preserve ancient processing traditions and care deeply about their environment. They put their heart and soul into the teas they make naturally, says Subhasish.

As much as the conversation is on branding and experimentation, ultimately, what will make a brand like Folklore work is its impact on the community. Already there are plans to set up a bamboo cottage on one of the tea farms open for experiential travel. Assam has a lot on offer, from textiles to food, and of course tea. “We want to bring people,” says Subhasish. We want to show the things that are going on here. That it’s not only tea, but a lot of associated cultural elements too.” He talks about the vision to make the area an open museum, where “the entire place can act as a museum, all the houses can act as a museum and the traditional tools which are used in the processing are living heritage.”

Subhasish describes Folklore as a “passion project.” Perhaps that’s what Assam needs more of, passionate marketers who can join hands with farmers to create quality teas and find a market for them for the greater good of the community. And if it includes nudging local preferences towards better tea for their consumption, that’s a bonus.

Trouville Black Tea

People have spun stories on my genesis.

Was it a monk who discovered me? or

Was it a king who dropped me in boiling water?

Yet my origin is unknown

Since then, I have grown

And grew and grew some more

Moving across spaces and borders

A living chronicle of several cultures.

I’m Trouville. I was found through pure chance.

— Subhasish Borah

Share this post with your colleagues.

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.

https://feeds.sounder.fm/10363/rss.xml