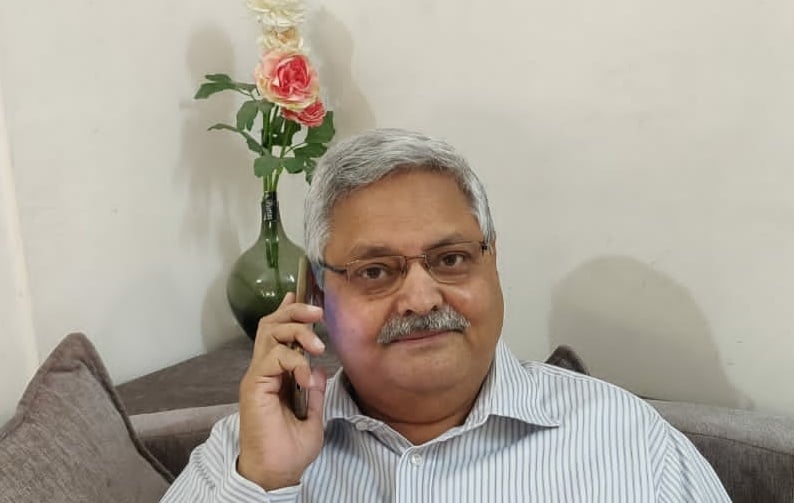

Rajiv Lochan is the founder of the Doke Tea Estate in Bihar, a non-traditional tea-growing region bounded by West Bengal and Nepal. India no longer requires permits to grow tea, a policy decision driven by increased domestic demand. Lochan foresaw the need to open new tea-growing regions years ago and began acquiring land along the Doke River in 1998. Since then, Lochan’s marketing mastery and tireless promotion have literally put Bihar on the official map of India’s tea-growing regions.

- Caption: Rajiv Lochan, founder Lochan Tea and Doke Tea Estate

Hear the interview

The Rise of India’s New Tea Growing Regions

In 1850 after the British established the Tukvar tea plantation in Darjeeling, India’s tea industry expanded rapidly, felling forests and flattening hills in Assam and terracing the Himalayan foothills to meet global demand.

To fill London’s warehouses, growers planted the Dooars and Terai, much of West Bengal, and the entire length of the Brahmaputra Valley in Assam. In 1940 there were 500,000 acres under tea; by 1960, there were more than 800,000 acres (329,000 hectares) under tea.

Exports rose steadily but beginning in the 1950s domestic consumption climbed even faster. In 1960 India exported 195 m.kgs of tea and consumed 115 m.kgs. Household consumption as a percent of India’s gross domestic product peaked that year at 87.4% percent. Ten years later, exports remained flat at 200 m.kgs, while domestic consumption had increased to 212 m.kgs. Today Indian consumers drink 90% of the tea it produces.

Until last year, registered gardens were permitted in only a few states. In 1960 the Tea Board of India recorded 160,000 hectares under tea in Assam. There were 82,000 hectares under tea in West Bengal (Darjeeling, Dooars, Terai, and West Dinajpur). North India, consisting of the Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab (Kangra), and Himachal Pradesh (Mandi), cultivated 255,000 hectares.

Bihar grew tea on only 725 hectares (about 1,800 acres under tea).

Growing regions are inherently blessed with tea-enhancing terroir. However, ideal soil conditions, altitude, and micro-climate still require the pioneering vision and gritty persistence of growers like Rajiv Lochan to achieve their potential. Rajiv graduated from university in 1973 with a master’s degree in organic chemistry. He spent his early career managing established gardens where his efficient management complemented his skills in cultivating award-winning teas.

In 1998, the Indian government, noticing the strong growth in domestic sales, issued permits to expand tea lands. Adhering to biodynamic principles, Lochan planted drought-resistant cultivars in the loamy soil along the Doke River. He now produces green, white, and oolong teas and black fusion, combining Assam and Darjeeling teas. It took him ten years to acquire and consolidate smaller plots into the Doke Tea Estate.

Dan Bolton: Rajiv, will you describe India’s domestic market for new regional teas?

Rajiv Lochan: We start with eastern India. Bengalis are very, very appreciative of Darjeeling tea. Calcutta has a direct connection to this growing region and is known to be a tea city.

It’s very unusual to find Biharis, who like orthodox Darjeeling. They are now opening up; yes, this is something good.

Doke Black Fusion is a handmade Bihar tea, a mix of Darjeeling and Assam. That’s why we call it fusion. We sit right in front of Darjeeling, and the cold winds coming from Darjeeling cool the plains for a more delicate tea. Doke has an amber liquor, fragrant aroma, and sweet taste, complex. Mixed together with the strength of Assam, it is full-bodied, slightly bitter morning tea.

Dan: That suggests terroir is important to their buying decision.

Rajiv: They understand; they listen. They’re very appreciative, they come in with questions, and they take the samples. I have a sample pack of about 10 grams which I sell for 60 rupees. They sometimes buy 600 rupees worth of packets.

“We produce very little on 10 hectares but we source teas from all over the region to make different blends and then package it. So we handle about a million kilos of tea every year.”

– Rajiv Lochan

Dan: Where do customers get their first taste of teas grown and processed in Bihar?

Rajiv: Online. Not many stores stock all these teas, and it is very easy to order online.

Specialty teas are only available in the big cities with lounges and specialty tea shops. I would not say even many of the tea specialty shops.

Amazon has taught India how to sit at home and order very, very comfortably and has created online shopping. All the ladies are very happy sitting at home buying whatever from this thing. Many buy to experiment. Yeah, Amazon has done wonders in India, successful like Coca-Cola.

Dan: Are the websites built by local brands sophisticated? Is delivery by mail or courier?

Rajiv: Teaswan. That’s our website. They do everything online; we do everything else. They handle the ordering and the total thing collection money and all.

Dan: How long does it take online customers to get their tea?

Rajiv: Maximum three days. Three days is very fair. We also use FedEx, DHL Blue Dart Express, and UPS. Siliguri, since the pandemic is very, very conveniently connected.

Dan: Tea from non-traditional growing regions like Bihar is now accessible but still not well known. Your innovative processing and tireless marketing of green tea and oolongs have earned the brand an international following, representing only a small volume of the million kilos you process locally. You can get higher prices overseas, but in a CTC (cut, tear, curl market), pricing is critical. According to the Tea Board of India, only 22% of Indian households spend more than INRs200 rupees (about $2.50 US per month for tea). What price do you charge local consumers?

Rajiv: Our 250 gram CTC sells for INRs 70 to 90 per pack. Tata costs almost the same, but the quality is better than Tata. The reason for people buying outside Tata is the quality. There are four or five local brands available from Siliguri, so people are not switching, and we find it very easy.

There are now seven factories in Bihar. There are 20,000 hectares under tea, and the total production is 25 million kilos. We package our teas in Siliguri, and most of our market is nearby in Bihar so that we can keep the quality. The shopkeepers prefer stock that is easy to sell.

Quality control is not that difficult; we have one system for packaging one mindset for our local CTC pack. Green tea orders are bigger than Darjeeling. When it comes to exporting CTC to China, we sell bulk 20 tons to the container, maybe 25 containers to one company and ten containers to another company.

We produce very little from the 10 hectares at Doke, but we are basically trading; we are sourcing teas from all over the region to make different blends and then packaging, so we handle about a million kilos of tea every year.

The sourcing people know that we can keep supplying them with the same blend throughout the year because we will source it from hundreds of people. We do our blending, tasting hundreds of samples, then giving them a standard blend that they want throughout the year.

Producers like Williamson Magor walk into the room, and they always say, ‘we are the third-largest producer of India,’ or ‘we are the second-largest.’ Being a very big producer, he’s going to sell only his produce, which he can give a little cheaper than us because he can manage his cost of production. Our cost is the total of buying from many smaller growers at rates that are profitable to the producer himself. Growers might have less overhead lower labor expenses. So, these are two different competing economics that the big buyers understand.

The domestic tea market in India is still not mature; this is just the beginning. The entry of more and more players from different regions will change the scenario, but India is a huge market, and if it opens up, it will really solve the industry’s problems.

Related

Doke Tea Estate

Link to share this post with your colleagues

Signup and receive Tea Biz weekly in your inbox.