The coronavirus outbreak is causing logistical havoc in advance of the world’s most valuable tea harvest.

“All parts of the country (except Hubei Province) are gradually returning to work and production under the guidance of the tea district government,” writes Tea Weekly.

Hubei Province, an important producing region, remains under lockdown with 2,500 (2,467) deaths, and 80,000 (78,914) confirmed cases of the fast-spreading epidemic centered in the city of Wuhan.

“China is reeling from the outbreak of novel coronavirus-caused pneumonia,” according to Cai Jun, secretary general of tea with the China Chamber of Commerce of Import and Export of Foodstuffs, Native Produce and Animal By-Products (CFNA). CFNA is an influential trade association that operates under the supervision of China’s Ministry of Commerce.

Setbacks are not due to illness or deaths of tea garden workers; it is the result of a national effort to limit travel, close factories, ban public gatherings and shutdown bus, train, air, and subways to prevent the virus from spreading.

“As far as I know, Chinese tea people are all safe and sound, which indicates that drinking tea helps to strengthen immunity,” writes Mr. Cai.

China’s tea industry saw this coming, according to tea retailer Austin Hodge, founder of Seven Cups Fine Chinese Tea in Tucson, Ariz. Hodge, who imports tea direct from China, recalls the SARS epidemic in 2003. The Chinese learned valuable lessons from that outbreak, which killed 774 globally.

“No tea is going to waste. They are not plucking if they cannot process,” explains Hodge, who praised the Chinese for “making all the necessary adjustments.”

“In rural tea country, the real issue isn’t the virus; it’s the lockdown and logistics. Everybody is local. They don’t have to travel anywhere,” he said.

He expects his first tea of the year to arrive on schedule in a week or two.

Procedures at China’s largest tea company factory in Erhai are typical. The plant resumed operations Feb. 13 as 700 workers were screened for fever, completed and signed a personal health commitment promising to wear masks, disinfect their hands and periodically visit one of six health test points. Upon entering the factory, they scanned the “Yunnan Epidemic Prevention” QR code with their cell phones, activating a cell phone (WeChat mini app) that tracks their movement and warns employers if they have encountered someone who has come down with the virus.

Effective Feb. 11, all Yunnan residents must scan a QR code to enter and exit public places, including residential complexes, markets, malls, hospitals, and public transit hubs. “No name, ID or other content is stored,” and Yunnan promises to destroy the tracking data once the virus is contained.

A factory manager estimated the increased security reduced productivity by 10%.

In the southern-most tea gardens where the harvest is just beginning, those who prune and pluck tea are required to wear masks and are not permitted to form groups. They must keep a minimum distance of 10 feet apart while working.

The China Tea Circulation Association reports that specialty harvests began Feb. 10 in Gaoxian in Sichuan and on Feb. 20 in southern Zhejiang (Wenzhou and Lishui).

“Under the epidemic situation, while doing a good job of prevention and control, multiple tea-producing areas and companies across the country have also organized tea farmers to start the first batch of 2020 spring tea picking,” according to the association.

“We’re not in picking season yet, so the virus hasn’t had much effect on the tea production and international trade. Although it does affect the sales, it’s overall manageable,” writes Mr. Cai.

Retail Impact

Grocery stores and supermarkets remain open, and food and beverage delivery are permitted, but the lockdown has cut foot traffic at China’s premier tea malls to a fraction of normal.

“When most tea markets are not open, companies are encouraged to sell online and micro-businesses,” advises the Agriculture and Rural Bureau of Yuzhou District as reported on the Sichuan News Network. Production of Chuancha in Yuzhou is projected at 1,800 metric tons valued at more than $42.5 million (RMB300 million).

More than 500 million Chinese drink approximately 1.9 million metric tons of tea annually, according to the China Tea Marketing Association. The domestic tea market is valued at $18 billion.

During the crisis, overall retail sales are being stripped of $144 billion a week, according to China’s Evergrande Think Tank (as reported by Forbes).

The impact thus far is most significant in congested urban areas. Every province, including Tibet, has reported cases of Covid-19, but tea regions were spared the initial brunt of the epidemic. Hubei reported 64,084 cases and 2,346 deaths.

Enshi tea producers are the closest hot spot, about 500 kilometers west of Wuhan. Plucking generally commences March 15 on Wufeng Mountain. Enshi is a green tea region, one of the few that specializes in steamed green teas. Train and bus service was suspended in January, all 70,000 cinemas in the province were closed, and public gatherings were forbidden. Only grocery stores, gas stations, drug stores, and hospitals are operating.

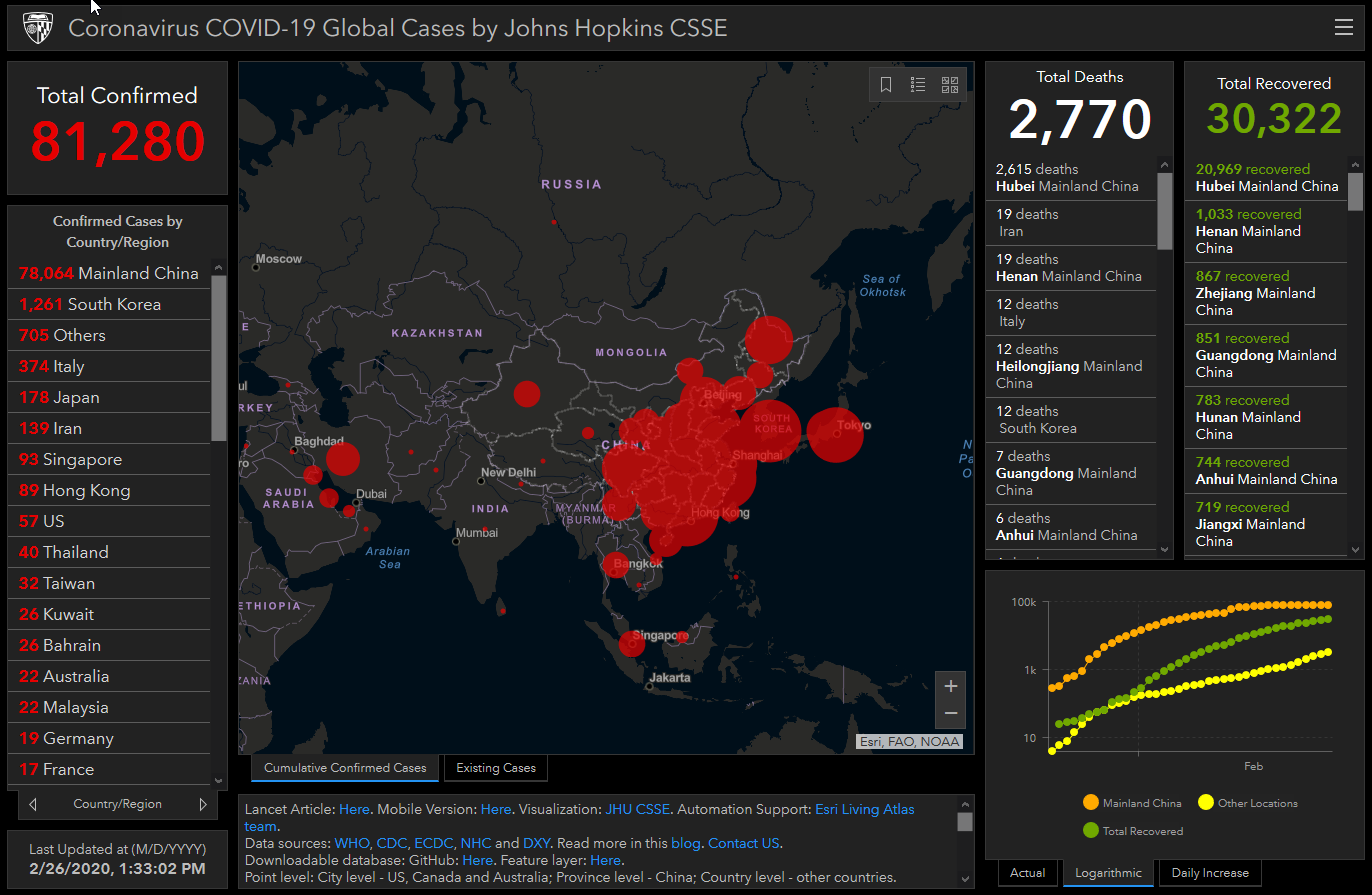

Johns Hopkins is tracking cases globally.

Generally speaking, the spread of Covid-19 in tea growing areas is slow, and infections in neighborhoods and local outbreaks are comparatively rare. Covid-19 cases in other places such as Enshi and Shennongjia are still attributed to imported cases, and the risk of spread is relatively low,” according to Epidemiologist Dr. Liang Wannian, Beijing’s health chief. His responses to questions from reporters were posted by the State Council of Information Office in Beijing.

How Bad Could It Get?

In addition to tea and coffee, Yunnan is one of the most important growing regions for cut flowers. Harvesting flowers is time-sensitive, and Valentine’s Day represents a significant but fleeting business opportunity.

Fresh-cut flowers from Yunnan are exported to 46 countries and makeup 70% of domestic market share in China’s major cities. Growers earn $64,000 (RMB450,000) per hectare on average selling flowers for $0.20 (RMB1.43) per bloom.

This year the timing could not have been worse, resulting in big losses due to a critical break in the supply chain as trucks, trains, and flights were suspended.

The magnitude of the problem became evident in early February at the Dounan Flower Market in Kunming. Dounan is the largest fresh-cut flower market in Asia. During the period Jan 27 to Feb 5, trade volume in the market slumped 95% to $61,355 (RMB431,500). Sales were 4.78% percent compared to the same period in 2019. Dounan sold 6.53 billion cut flowers valued at RMB5.4 billion last year.

This was compounded by the fact that 50 million consumers were confined to their homes in the Wuhan region and that offices nationwide were closed for as long as two weeks beyond the traditional spring festival travel holiday. The auction was shut down for several days, re-opening Feb. 10.

One-third of Yunnan’s annual cut-flower revenue is earned in February, according to Wang Jihua, deputy director of the Yunnan Provincial Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Mr. Wang estimates that the loss of Yunnan’s flower industry, including supporting industries such as logistics, during the special period will reach RMB3 to RMB5 billion ($425,000 to $715,000).”

Transport options were cut by 90% during the height of the lockdown and are only now being restored. Roadblocks prevented entire villages from access to larger cities and towns. Tea faces a less critical timeline?processing must begin within four hours once leaves are plucked?but the logistics of transportation are the same.

Phil Orlando, Chief Equity Market Strategist and Head of Client Portfolio Management at Federated Investors, told Bloomberg Newsweek the world’s stock markets had not indicated the true impact on trade. “In my humble opinion, it will be bigger than people think,” he said.

Orlando was proved correct Feb. 25 when stock markets globally suffered steep declines.

Looking Ahead

The last three weeks of February were the first in which the number of patients cured of the disease outnumbers those who contracted Covid-19. It is too soon to declare an end to the crisis, but progress is evident.

“The epidemic is under effective control due to the Chinese government’s prevention and control measures,” writes Mr. Cai. During the lockdown, “most people work from home except those who work in the sectors responsible for the supply of the necessities. We have full confidence and capability to win this fight against the epidemic,” he said.

Mr. Cai said that China’s major tea companies “have shown a dedication to fighting this virus by donating money and necessary supplies to those affected areas.” CFNA was forced to postpone three tea conferences scheduled for March, and several tea fairs, including the spring edition of the Global Tea Fair, are being rescheduled.

Sources: Bloomberg Newsweek, China State Council of Information Office, Xinhua, Tea Weekly

China’s Four Tea Growing Regions

China’s 80 million rural tea laborers annually produce 2.56 million metric tonnes of mainly green tea on 3 million hectares of land. Their effort results in half of the world’s annual tea production of 5.2 million metric tons.

Domestic sales by volume are mainly of green tea, but many localities, including Quimen, Fuzhou, Wuyi, and Fuding (in Fujian province) and Pu’er in Yunnan Province, specialize in the production of high-value oolong, white, jasmine, black, and post-fermented teas.

The China Tea Marketing Association estimates 63.1% of domestic sales are from green tea; Pu’er teas represent 14% of sales; oolong represents 11.1%; black tea accounts for 9.9% of sales and white tea for 1.5% with yellow tea estimated at 0.4% in 2018. The Chinese will drink 670,000 metric tonnes of tea in 2020, for which they will spend $18 billion.

Tea plantation acreage has grown substantially since 2006 with most new plantings south of the Yangtze River valley in Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, and Hubei provinces—the four best-known tea growing regions.

Jiangnan

Tea grown south of the Yangtze river spans several provinces. It is called Jiangnan and includes Zhejiang, Jiangxi, portions of Anhui, and Hunan provinces. It is the largest tea producing region by volume. Hubei province is split with Wuhan north of the Yangtze and Enshi, south of the river near the Wufeng Mountains. Wuhan is 850 kilometers inland from Shanghai, which is at the mouth of the Yangtze.

Jiangbei

Tea grown north of the Yangtze (Jiangbei) spans Henan, Shandong and northern Anhui. Jiangbei is China’s smallest tea growing region.

Huanan

South China is known as the Huanan growing region. This superior tea growing region spans coastal Fujian, Guangxi, and Hainan island. Fujian is the most important tea producing province by value.

Xinan

Tea in Southwestern China within the Xinan region is grown in Guizhou, Yunnan, and Sichuan provinces. The earliest teas are plucked in late February in the semi-tropical portions of this zone bordering Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar.